Over the last year, the rupee depreciated against the dollar – by just over six percent. The rupee’s depreciation would’ve actually been much steeper, if the dollar itself wasn’t also getting weaker – depreciating against other currencies.

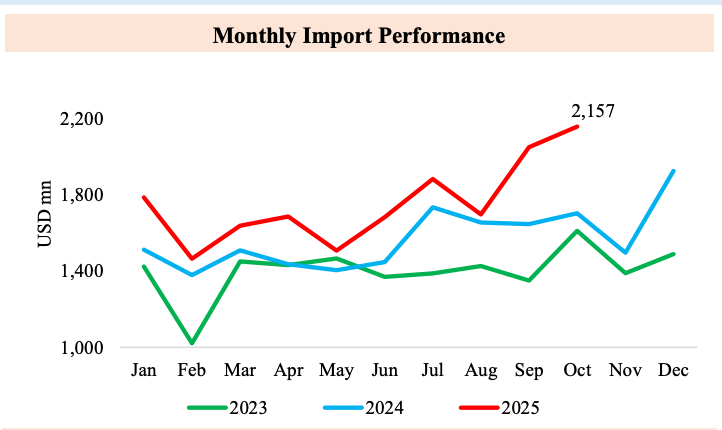

From boardrooms to Pettah there is consensus on the cause for the rupee’s fall: lifting the vehicle import ban early this year. Thus far, vehicle imports exceeded $1.2 billion. Last year they were virtually nil. This billion dollar plus increase in the import bill led to greater demand for dollars, the moneyed men opine – causing the dollar’s appreciation against the rupee.

This is partly true. Resuming vehicle imports mechanically raised demand for dollars in the short run.

However, they further argue that vehicle imports resuming means the rupee will continue to slide. This view is wrong. While the resumption of vehicle imports created a short-term spike in FX demand, the more persistent pressure on the rupee is caused by money printing.

This is because, outside the short-term, the rupee’s depreciation is not determined by whether people are buying vehicles or not. Other things being equal, any increase in spending on vehicles would be offset by reduced spending on other imported goods.

This is because, under normal circumstances, people’s spending is limited by their income. If they spend less on one thing, they spend more on something else. This is especially true in Sri Lanka, where people generally save little. 80 percent of household income is spent on non-discretionary spending like food, transport, and housing.

Therefore, vehicle imports or not, people would have spent roughly the same amount, creating a consistent import bill. That wouldn’t have impacted the exchange rate.

So the real culprit of the current depreciation must be something else. I argue it’s the central bank’s money printing.

Printing money

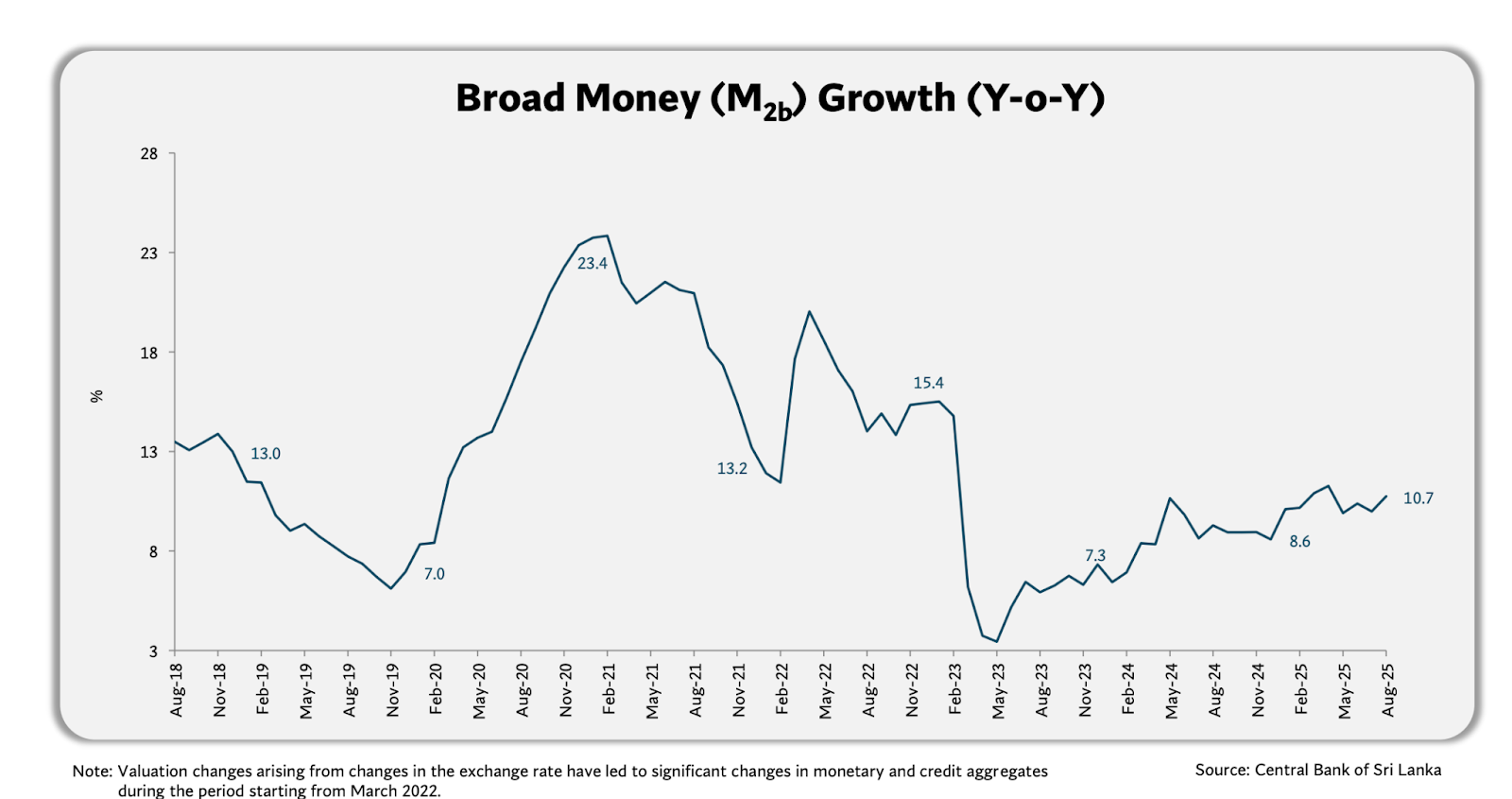

Between September 2024 and January 2025 the Central Bank created around 100 billion rupees buying securities from domestic banks. The vehicle import ban was lifted in February 2025 making it easy to misattribute the effects of the ban. It continued to create more money in the first half of 2025 by buying foreign exchange and entering into swaps with commercial banks.

Unlike a normal bank the Central Bank does not accept customer deposits yet they are able to buy foreign exchange and securities. This is because the Central Bank didn’t buy the bonds and dollars through a normal bank transfer from their bank account, like you and I buy things. Rather the Central Bank paid for the bonds or dollars by an accounting entry, crediting the domestic bank’s account at the Central Bank. This is new money created out of thin air with no underlying economic activity (for more details on how the central bank printed money without printing money, see below).

The new money created through these actions has accumulated in the banking system. It is now being lent out. Private credit grew by over nine hundred billion rupees in the seven months to July 2025.

More money = more imports

This borrowing leads to higher consumption by citizens and higher investment by firms. Both result in more imports.

When people and businesses spend more – whether on things produced on the island, or imported ones – they need more dollars. Even higher spending on domestic products, such as local rice, may also increase import demand. After all, producing rice requires imported fertilizer, pesticides, machinery and fuel.

When the Central Bank adds new money to the banking system, it makes it easier for banks to lend and for people to borrow and spend. But the amount of goods available does not automatically expand in step with this new spending power. As a result, some of that extra spending spills over into imports.

That raises the demand for dollars at a time when the supply of dollars has not changed much. In this situation, more rupees are trying to buy the same amount of foreign currency, which puts downward pressure on the rupee.

That’s why simply lifting the vehicle ban would not, on its own, have raised total imports, if the Central Bank had not created new money. Without the extra liquidity injected by the Bank, households would only have been reallocating their existing spending: buying vehicles, but cutting back on other goods. The overall import bill would have stayed roughly the same. But because the Central Bank did create additional money, people now have more spending power than before. That extra spending is what is pulling in new imports, including vehicles.

Sri Lanka’s experience since 2020 shows that when the Central Bank is printing money import bans do not work. Sri Lanka was already in a severe foreign exchange crisis from 2020 onwards, yet the Central Bank continued to print money. From April 2020, the government kept tightening import controls, hoping to save foreign currency. But because the Central Bank was increasing money supply at the same time, people still had the spending power to buy imports.

The pressure simply shifted to whatever goods were still permitted. As a result, total imports did not fall. In fact, they rose to a three-year high of US$21.6 billion in 2021, compared with US$16.1 billion in 2020 and US$19.9 billion in 2019, despite the bans. This shows that when new money is created, it continues to pull in imports regardless of restrictions. Import bans can change which goods are imported, but they cannot reduce the total import bill unless money creation stops.