“Ministers come, and ministers go.” — Sir Humphrey Appleby, Yes Minister

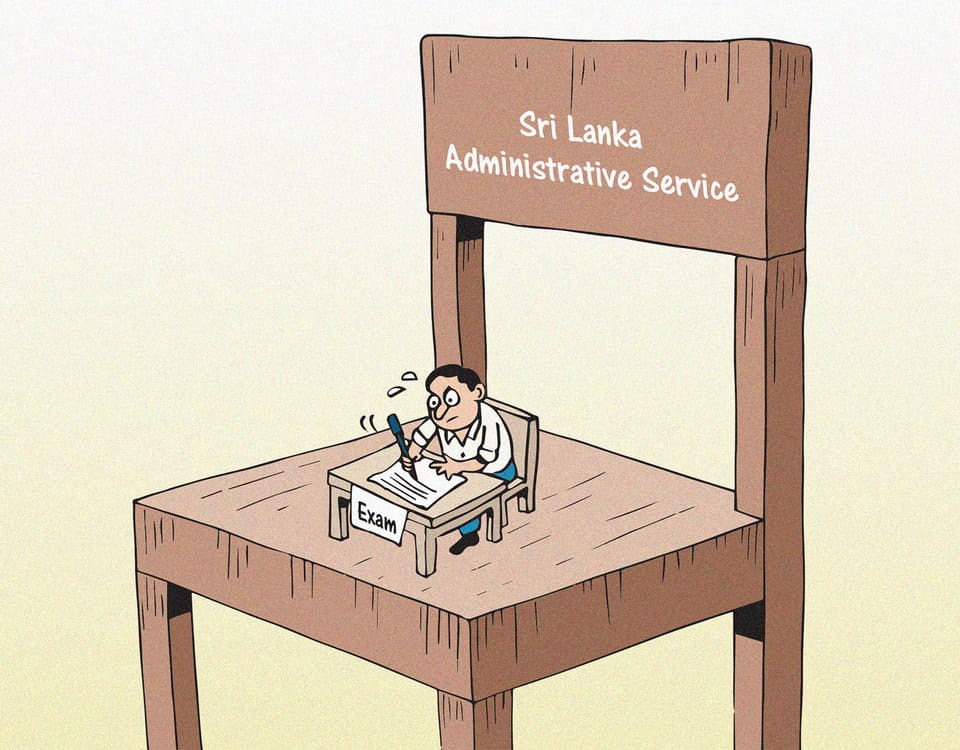

Saying the people who really run the country are the Sri Lanka Administrative Service’s 2906 men and women isn’t much of an exaggeration.

Ministers give speeches and cut ribbons. They’re also in charge of high-level policy. But they do so on the advice of civil servants. Civil service mandarins also translate ministers’ policies into plans, and make those plans a reality (or not). The top bureaucrats further manage over 1.3 million public sector staff.

The influence and power of the administrative service, or SLAS, is unmatched by any other group of civil servants. They are the steel frame of the Sri Lankan state, pre-eminent among different services like the foreign service, revenue service, and scientific service. The commanding heights of the government, just over three hundred of the most important posts, are reserved for them. This small group of people — along with the president, MPs, and judges — hold our collective fate in their hands. If they succeed, we succeed. If they fail, we fail.

This is why they must be people of extraordinary talent, exceptional commitment, and unquestionable integrity.

Flawed exams

Unfortunately the best and brightest aren’t staffing the SLAS. Those who deal with civil servants across the developing world — diplomats, development bankers, and investors — are surprised, sometimes shocked, at the poor quality of Sri Lanka’s top civil servants. Their dismay arises from the contrast with the talent available on the island, and compared to neighbours like India where the Indian Administrative Service, or IAS, is staffed by some of the finest civil servants in the world.

They would be less surprised if they saw the SLAS entrance exam. The open entrance exam is the entry route for three-quarters of SLAS recruits, and can be attempted by any university graduate under the age of 28. The remaining quarter is selected from within the public service.

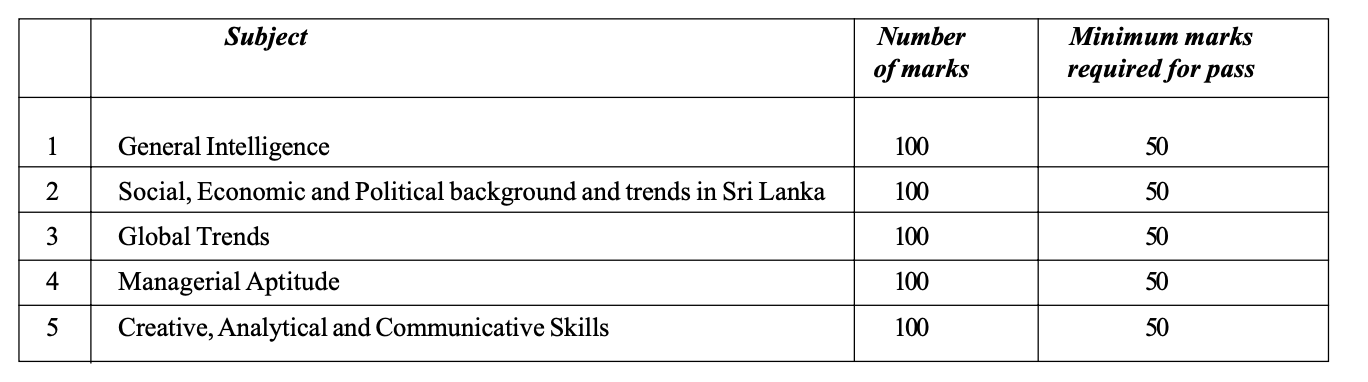

The exam has five parts and, along with the interview, is the sole assessment used for entry into the service.

The intelligence past paper is not made public by the exams department. The other past papers reveal serious mistakes and senseless questions, raising grave concerns about the effectiveness of the SLAS’ recruitment procedure.

The exam insists on testing the recall of obscure and useless facts — not powers of reasoning. Even worse, the memorisation prowess it tests ranges from the banal to the trivial. Consider these multiple-choice questions, which include:

the banal;

“Which is the Sri Lanka Telecom hotline for which complaints on consumer goods should be made?”

the absurd;

“Which one of the following of the United Kingdom grows Tea for the first-time successfully at a commercial level at present: Scotland, Wales, England, Northern Ireland?”

the racist;

“What is the Asian country where citizens who made workaholism the life style as a national characteristic?”

the prejudiced;

“The Youth of Sri Lanka which has inherited an ancient culture is facing a cultural conflict because of the influence of the Western culture. Examine four remedial measures that could be taken to rescue the youth of Sri Lanka from this situation.”

all the way to the downright incomprehensible;

“State should always be moral” is an accepted norm.” State two ideas to describe the concept of morality.”

The question papers are also plagued by spelling and grammar howlers, some of which can be seen in the questions above.

Examining across countries

The contrast between SLAS exams and the exams of equivalents overseas is pronounced. Consider, for example, the general knowledge section of India’s Union Public Service Commission, or UPSC, exam that’s used as the entry exam for India’s top civil servants, including the IAS.