Hours before Cyclone Ditwah hit a Nuwara Eliya school principal’s phone beeped. He had just got an SMS from the Disaster Management Centre, or DMC. The alert said heavy rains and landslides were expected for the district. “What can we do with that? Nuwara Eliya is always a disaster area,” he says from his school – now a temporary shelter for 280 people. They ran at the last minute, with nothing, as the earth moved around them.

“The message didn’t say specifically these villages will get hit. That’s what they should have done.”

Life-saving tech still being built

But the meteorology department doesn’t have technology to make highly accurate, localised forecasts. Instead, to make predictions, the department uses global data shared by meteorological agencies across the world – supplemented by local data from 23 stations.

To make accurate, localized forecasts – especially for how much it will rain – the department’s head Athula Karunanayake says they need one key piece of equipment: doppler radar.

Doppler radar can determine the quantity and location of rainfall, approximately two hours prior. Currently, the department is only able to forecast that rainfall will exceed a certain amount. It cannot, for example, say if it will be 200 mm or 250 mm.

Doppler radar can also predict rainfall for specific villages, such as Hanwella – rather than the current broad predictions, which are for a province as a whole, such as Sabragamuwa. .

But Ditwah brought some of the highest rainfall recorded in the island’s history — reaching more than 540mm in Matale.

Doppler radar is currently being constructed in Puttalam, covering the country’s west. Karunanayake wants another in Pottuvil. Having two radars will cover the entire island, and allow the department to ‘nowcast’. This method leads to accurate, highly localised forecasts. Government departments like the DMC, irrigation department, and the agency responsible for landslides, the NBRO, can then make more informed decisions.

“That two hour window with nowcasting is very important. When we inform government agencies they can minimize loss of life and economic damage,” says Karunanayake.

The toll of imprecise forecasts

Ditwah left 215 landslides in its wake, burying entire villages under mountains of earth. Families, friends, and neighbours perished in large numbers, with search for the dead still ongoing.

Since they are unable to precisely predict how much rain will fall where, the NBRO isn’t able to issue landslide warnings as effectively as they would like.

“We predict that landslides will happen when the rainfall exceeds 150mm,” said an NBRO source who requested anonymity. “But there was 400 to 450 mm of rain within 24 hours. That was part of the problem.”

Broad landslide warnings covered almost the entire hill country. But still, some landslides caught the NBRO by surprise.

In Matale’s Rambuk Ela, two villages were stacked, one on top of another, on a slope. The bottom village got a warning. So,in search of safety, one lady moved up to her relative’s house in the higher village. But, the earth gave away at the hill’s top, killing her and her relatives.

“If we tell people to evacuate we should be able to say exactly where is safe,” said DMC preparedness director Chathura Liyanarachchi. “People have to trust us. But we couldn’t reliably do that.”

The irrigation department too struggles to make decisions without localised forecasts.

“Precise localised data is essential to operate reservoirs in disaster,” said L. S. Sooriyabandara, the department's head of hydrology. He explained that the department can’t risk releasing water early from tanks as empty reservoirs can affect food cultivation and security.

“I am not blaming the meteorology department. They are working with the technology they have. But without precise data showing the quantity of rain above a specific tank, we can’t make a decision.”

Considering the forecast and actual rain data, the irrigation department was gradually releasing water from reservoirs. But, with the high rainfall, several spilled over. Ultimately, people had to be airlifted out of flood water by the airforce, some after spending over a day on rooftops and coconut trees.

The forecast that was

Meteorology department head Karunanayake says that they started monitoring low pressure areas around Sri Lanka by mid-November, when tropical cyclone season starts.

Preparations for storms included meetings with stakeholders like the DMC on 17, 20, and 23 November.

But the DMC didn’t plan for an intense cyclone. Meteorologists weren’t able to confirm a cyclone at that point. Referring to a controversial appearance on Ada Derana on 12 November, Karunanayake said: “There were several low pressure areas and some that even passed us by. That is what I was discussing then. I did not name it as a cyclone then because it simply wasn’t one.”

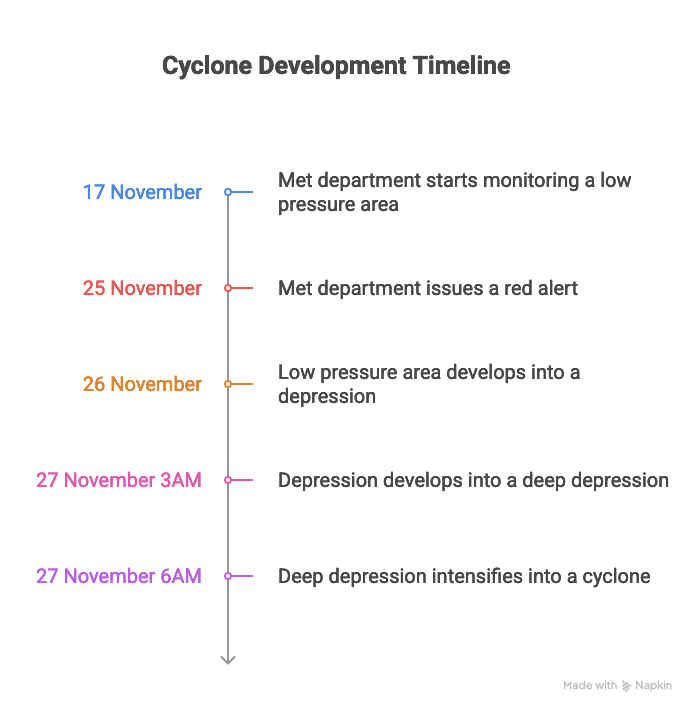

By 17 November, the met department was monitoring a low pressure area southwest of Sri Lanka. They were assessing whether it would develop into a depression, deep depression, cyclonic storm, or super cyclone.

Dr. S. Pai, a scientist at the Indian met department that shares regional data with Sri Lanka, said given Sri Lanka’s size, cyclones would typically cross in a few hours – or at most, a day.

“Northward winds are slower than those going east to west,” he explained. “So the cyclone took a long time, two days, to move across Sri Lanka, resulting in worse destruction.”

Since Sri Lanka is surrounded by water, the cyclone was able to gather a lot of moisture and intensify, rather than weaken, as is typical for its kind after making landfall, he added.

It is very rare for cyclones to form this near the equator and so close to land. Forming so close to Sri Lanka, Cyclone Ditwah remained strong, explained Dr. Pai. interaction between Ditwah and the simultaneous Cyclone Senyar near Malaysia further complicated predictions, says a former official at the Sri Lankan met department.

Downward communication

At 10:30PM on Tuesday, 25 November, our met department issued a red alert for nine districts, cautioning that the low pressure area was likely to develop into a depression. This alert activates government apparatuses like the NBRO.