In the past, Ella was just another station on the scenic train ride to Badulla. From their carriage window, tourists took it in for a few minutes before arriving in Badulla — to catch the bus to Arugam Bay. Only a few tourists would trickle down to Ella, to either visit the Ravana falls or climb the Ella rock.

With no hotels to service them, Suresh Rodrigo, an old-time hotelier in Ella, says his mother, along with a few other women, started homestays. To attract more tourists to the tiny village, Rodrigo and his friends would take the same train to Badulla. They pitched the then unknown Ella to tourists as a mountain village with fresh air — “oxygen”. For travellers today, a Lankan sojourn isn’t complete without dropping into Ella, and trying experiences as varied as the excitement of ziplines or the calm of mountain yoga.

As visitors started flowing in, a bustling town centre rose, with restaurants topping the ‘best’ lists in the world. It became one of the few destinations which rose to the significance of traditionally-popular beach destinations. But its infrastructure didn’t keep up.

The mountain village’s unique selling point was that it was rich in “oxygen”, due to Ella’s high elevation and lush vegetation, says Sunil Premasiri, one of Ella’s oldest hoteliers. Yet today, Ella is struggling to sell the same product. As travellers enter Ella, they now see, and smell, a new mountain. A peak of garbage looms over the town’s entrance, marring the greenery — the authorities, despite protests, chose to locate Ella’s waste processing facility there.

“How can we sell oxygen to the tourists when the first thing they see as they enter the town is a trash mountain?” questions Premasiri.

Despite repeated outcry, there’s no public car park. With only one narrow tunnel to enter Ella, on busy long weekends, vehicles sit in traffic for about three hours.

“The number of visitors isn’t the problem,” says Premasiri. The problem is that public infrastructure isn’t being built. Premasire — leading the town’s trade association since its inception — says they’ve lobbied multiple governments and state agencies to ensure the tourism product in Ella remains competitive. But progress has been slow.

Ella is unusual in that there are no major hotel corporations like Jetwing, Cinnamon, or Marriott — instead, local businessmen themselves built sought-after hotels like the 98 Acres. As more tourists came to Ella, people started sporadically building more hotels and homestays on the mountains, killing the view.

Again, Premasiri says the number isn’t the problem; it’s the lack of planning. He advocates for height restrictions, like in Nuwara Eliya.

Human v. leopard

The lush green mountains with frequent cool rains may feel endless from Ella, but just two hours away, they give way to the dry zone; where leopards and elephants roam the heated earth. And here lies Yala, the most-visited national park in the country.

Travellers are drawn to Yala in search of the elusive leopard. These owners of the park are proud, either haughtily refusing to move from the trail or shyly refusing to show their faces through the shrubs. To ensure visitors get to see the leopards — who aren’t always willing participants in the show — jeep drivers employ numerous strategies, like calling each other as soon as one spots a leopard, so a barrage of jeeps crowd in on one animal at once.

The “embarrassingly poor quality of visitor experience” means that he no longer visits national parks, says biodiversity expert Rohan Pethiyagoda. To factor in the tourism industry’s environmental sustainability, he advocates for destinations first tackling overvisitation.

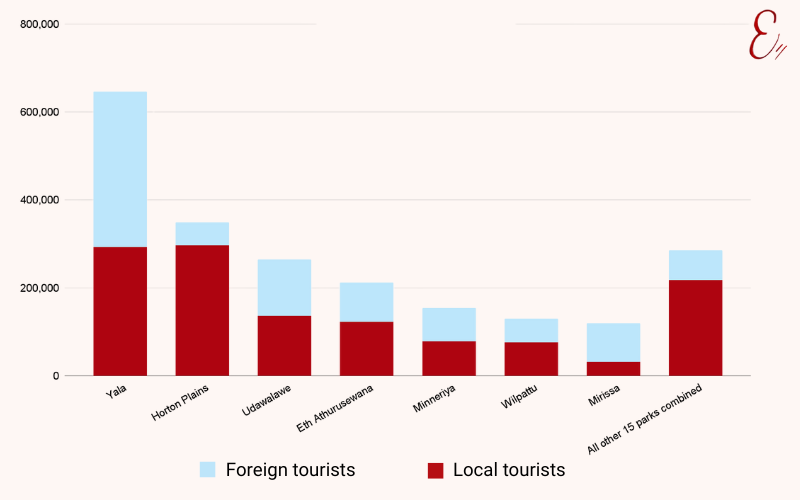

Where there is overvisitation, there is overvisitation by both locals and foreigners, he added.

Of the two million tourists who visited the island in 2024, nearly half — around nine lakhs — visited the country’s 23 national parks. But they crowded together at just a handful. Yala attracted over a third of them.