A review of the newly published economic history, ‘Kerala, 1956 to the Present’, by Tirthankar Roy and K. Ravi Raman

The Examiner has more opinions than it has staff. We maintain unanimity in our facts, not the inferences we draw from them. This examination is no exception.

Kerala’s and Sri Lanka’s histories have moved in tandem for centuries. From time immemorial, ships from Indochina carrying spices and silks rode to us on the monsoon winds. They waited on our shores for months till the winds shifted, bringing with them Arab dhows laden with horses and perfumes. East and West met, conversed, and traded. Over the last few centuries we both endured Portuguese, Dutch, and British rule which ushered in a plantation economy. Then, after independence, we cut ourselves off from the world. The new raj drove out foreign capital, nationalised the economy, and embraced state-led industrialisation.

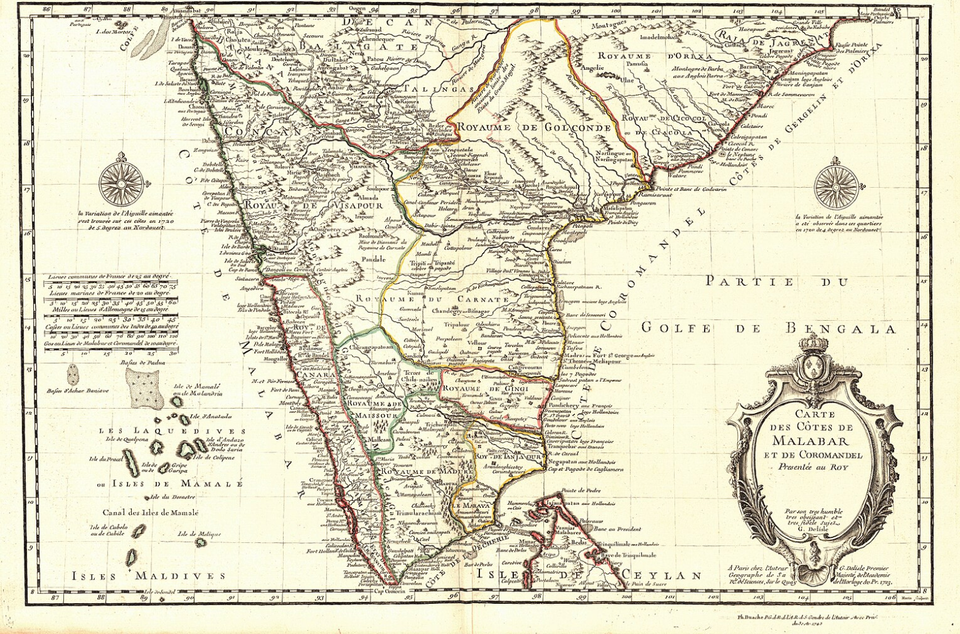

Sri Lanka is found at the foot of India’s south-east seaboard — the Coromandel as it was known. But, given our climate and culture, Sri Lanka often resembles India’s south-west Malabar coast, where Kerala is located. It is no accident that Jaffna Tamils were called Malabars in times past. So would it be strange if our economics were also more Malabar than Coromandel? Perhaps Roy and Raman’s Kerala Model is also the Lankan Model?

Both of us started at the same place. At independence, the economic structures of Kerala and Ceylon were nearly identical. The colonial state enabled global capital to forge an export-driven plantation economy.

The government sold land to tea and coffee planters, and built infrastructure like canals and roads. Loans from London financiers funded land clearing and planting.

Parts of Sri Lanka’s Coconut Triangle and Kerala’s coconut-growing Kannur are most likely reclaimed land created by draining swamps and building canals. Plantation factories heralded the industrial revolution, which was followed by railways transporting tea and coffee to the Colombo and Cochin ports.

These boom towns became Indian Ocean port cities par excellence — home to the usual cabal of British management agencies, commodity brokers, and banks.

An indigenous capitalist class also emerged; either as minor planters or offering ancillary services like bullock carting. Everyday workers too were not untouched. The universal embrace of capital and globalisation did not pass them by. The plantation economy significantly reduced dependence on subsistence farming. In Ceylon and Kerala the share of workers employed in subsistence agriculture was much smaller than elsewhere in India, where globalisation came much later.

This unusually early integration with the world economy was also paired with exceptionally vibrant missionary activity, chiefly directed at health and education. As a result Kerala and Sri Lanka had an early advantage in the export of labour services. Malayalees and Jaffnamen staffed the middle-ranks of imperial bureaucracy across the Indian Ocean. Education became the main vehicle of economic and social mobility.

The great retreat

Despite the sea-change of swaraj, the congruence of Kerala’s and Sri Lanka’s economic trajectory continued. However, with independence, the focus shifted to redistribution. Both seized capital and land from the hands of the plantation raj and wealthy indigenous landowners. Occasionally it was redistributed. Unfortunately in Sri Lanka, not very zealously. Much of the land was not given to the landless. It remains in the state’s hands to this day.

Soon after independence, the plantations were also suddenly cut off from the world. Roy and Raman’s description of Kerala is equally applicable to Lanka: “restrictions on the managing agency contract, employment of personnel from abroad, overvalued exchange, and a virtual blockage on foreign remittance and import of machines from abroad led to an almost across-the-board decline in the tea companies.”

In Sri Lanka’s case the plantations were also nationalised, leading to an even more precipitous decline in tea and rubber production. In both cases plantation worker wages did increase, often substantially. Nonetheless, capital and expertise departed. British, and later Sri Lankan planters, tea-tasters, and machine-operators left for emerging tea producers. Planters from Sri Lanka set up Kenya’s tea industry while Kerala’s entrepreneurs fled to the more liberal Tamil Nadu.

Industrialisation did not fare much better. Roy and Raman argue that, in Kerala, the state took the lead in industrialisation, creating islanded industries — businesses with few horizontal linkages or connections up-and-down the value chain. As a result, in their words, “with few exceptions, if any, public-sector firms made losses.”

The Sri Lankan equivalents were the likes of the Paranthan chemicals plant, Oruwala steel mill, and Embilipitiya paper factory. The causes were the classic problems facing state-owned enterprises...