The Examiner has more opinions than it has staff. We maintain unanimity in our facts, not the inferences we draw from them. This examination is no exception.

The upcoming budget doesn’t involve much budgeting. For the two fundamental questions a budget is meant to answer — how much to tax and how much to spend — are pre-ordained.

The appropriation bill, the annual law which authorises taxes and spending, more or less writes itself. 80 percent of government spending is rigid, devoted to salaries, pensions, welfare, and interest payments. They brook no amendment. On the revenue side, the IMF has clear conditions.

Instead the budget is the government’s annual economic policy statement, setting out its economic strategy and outlining its major initiatives. This is what is known as the budget speech, delivered by the finance minister in Parliament during the budget debate, on 7 November.

Implementation is the challenge

But writing that speech is the easy part. The greatest challenge for the government is not good ideas, nor is it political will. The greatest obstacle any government faces is implementation.

Reforms announced with fanfare in the budget speech are recycled year after year. New laws on insolvency, a holding company for state enterprises, participation in the PISA education rankings are all ghosts from budgets past. Disingenuity isn’t the cause, rather it’s a failure to deliver on these promises.

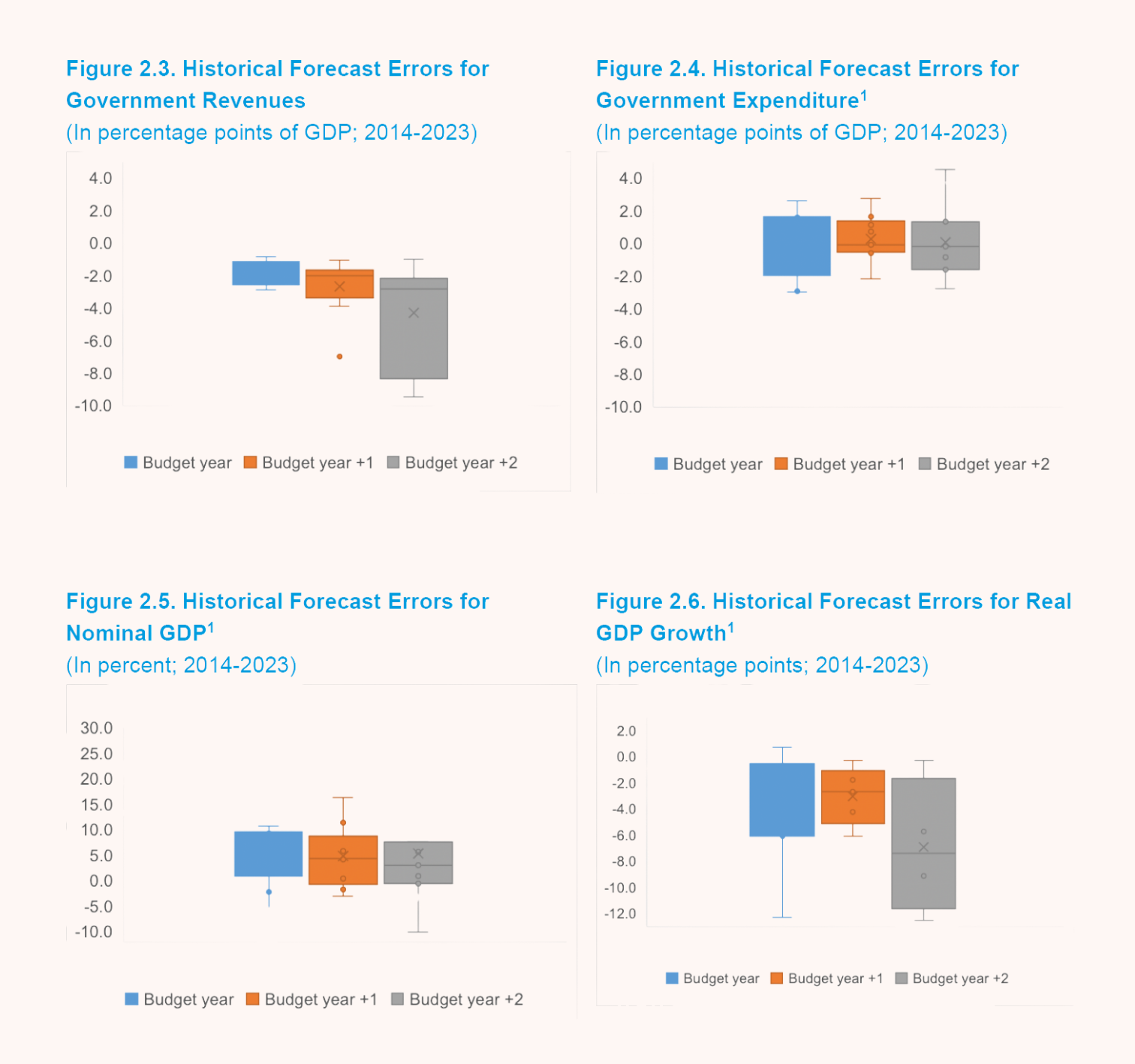

The problem starts with the budget estimates, which are consistently overoptimistic. Budget numbers are as fanciful as politicians’ election speeches. Mid-course, this results in ad hoc changes in spending and taxes.

Then there’s the budget speech itself. It’s prepared in secrecy by a handful of Treasury officials, without much consultation with other ministries. Policies and projects are sometimes not fully thought through. They often lack buy-in from the departments and agencies that implement them, says a former Treasury official.

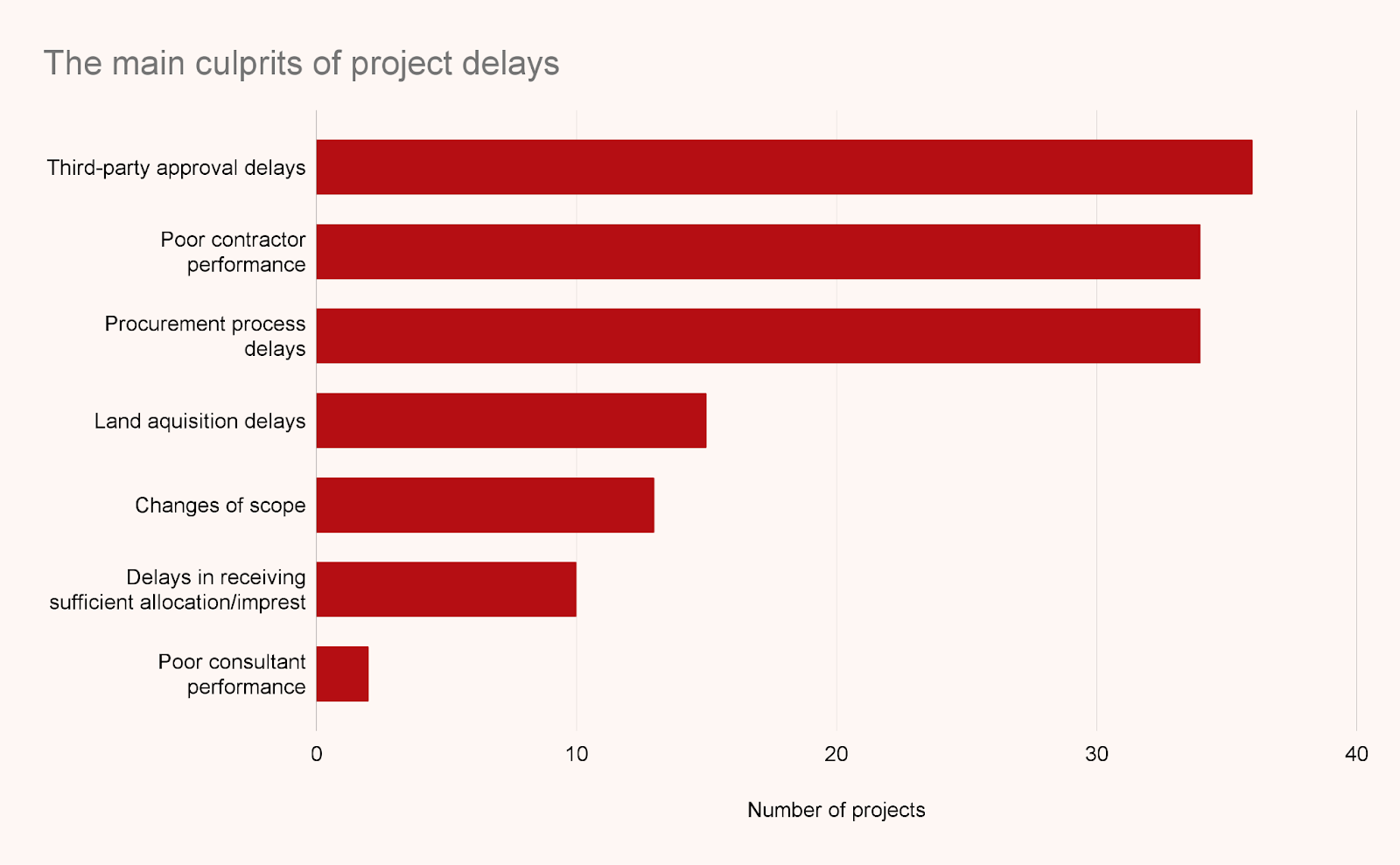

Even if line ministries start implementing a policy or project, execution lags due to poor planning. “Delays in the procurement process, poor contractor performance, changes in project design, and delays in loan disbursements” are the main culprits, according to a Finance Ministry report. The World Bank notes that “projects are not assigned a unique ID”, meaning they cannot be easily tracked over the project lifecycle.

Civil servants are scared of taking decisions. “Everyone is now afraid of signing anything,” says the former treasury official. They worry they will be dragged before commissions and courts when governments change, similar to what happened during the Yahapalanaya years.

Accustomed to a longstanding culture of political pressure to get anything done, they are now “extra careful” of displaying vigour, said a senior bureaucrat. Particularly given the government’s anti-corruption drive, civil servants fear being perceived as corrupt, if they are quick and effective in implementation.

Bribes and political protection sometimes greased a dysfunctional bureaucracy; without them, there is little reason for already underpaid civil servants to take risks.

Delays are costly

The costs of tardy implementation are real. Take public investment. Half the infrastructure development planned for last year didn’t take place. In July this year, Anil Jayantha Fernando, the finance and planning deputy minister, acknowledged that over half of last year’s public investment budget was not spent.

And in the first four months of this year, disbursed capital expenditure was actually less than in the same period last year, even though the economy is recovering. Such consistent capital underspending is a reason Sri Lanka’s stock of public investment ranked 143rd out of 166 countries on the last available ranking.

The government is aware that capex underspending is affecting the economy’s immediate growth and long-term growth potential. A Finance Ministry report noted: “allocations for projects in the transport, highways, ports, and civil aviation sectors show significant underutilisation.” Ironically, one of the projects categorised as ‘red’ — meaning severely delayed and thus underutilising funds — is the Treasury’s own Fiscal Management Efficiency Project.

Policy matters too

The great implementation challenge doesn’t mean that policy doesn’t matter. It does, a great deal. As implementation is so difficult and takes so long, getting policy right becomes even more imperative.