In the dead of the night, a long convoy of lorries carrying giant wind turbines slowly drove down the narrow causeway connecting Sri Lanka’s mainland to Mannar island. They entered the town but their passage was blocked by over 150 Mannar residents sitting on the road. Around 50 police officers, including the STF, armed with batons and shields violently dispersed the protestors. Three were hospitalised, and nine were arrested.

Hours before the violence, residents rose from dinner and set out towards the town. In the village of Pesalai, a 20 minute drive from the town, the church’s loudspeakers blared a warning. Rather than the usual prayers and hymns, the speakers announced that lorries were on their way to Mannar, carrying windmills.

The tip off had come from Vavuniya, where the windmill fan blades and other equipment had stopped on their long journey from China, through the Trincomalee harbour to Mannar island.

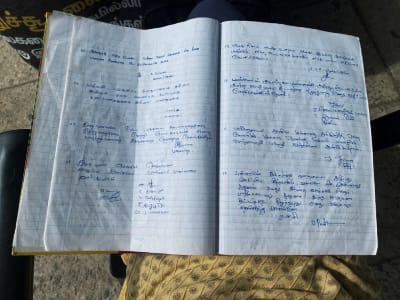

The midnight protest was sudden, but the ongoing daytime protests are well organised. For 62 days, the residents of Mannar have continuously protested ‘under the neem tree’, as their agitation site is called. Protestors mark their attendance in a log book, along with their reasons for participating. Led by Father Santhiyogu Marcus, a Catholic priest, the protest saw its highest turnout on Monday, with over two thousand in attendance.

They came to voice their fears on two topics: wind turbines and sand mining. With wind turbine construction currently underway, the mills are the protestors’ primary focus.

The Mannar public, particularly those living in Pesalai and nearby villages are distrustful as severe flooding upended their lives in recent years. They blame the floods on the 30 CEB wind turbines built in 2021 under the Thambapavani renewable energy project.

75-year-old Ganeshwary and her daughter K. Selvarani survive on their home garden in Olaithoduvai, where they cultivate various crops like beetroot, coconut, and pumpkin. But all 50 trees of their most profitable crop — murunga — died in last year’s floods. Murunga cannot survive for over a week under water, but the floods stayed in their village for three months.

“We have been here since 2004,” said Ganeshwary. “Never in my life has it been the way it was in the last three years.”

The villagers in Olaithoduvai, Karisal, and Kattaspathri have suffered displacement — primarily to India — during the war. For some, this is their ancestral home while others moved during the ceasefire from the Mannar mainland and Kilinochchi. They fear yet another displacement, this time due to environmental harms. Selvarani had to beg her mother, Ganeshwary, who was determined not to leave their village, to take shelter with her sister on the mainland.

Yet displacement is now their reality. Nithya and Suresh (names changed) stayed in the son’s school for weeks during the flooding last year, taking with them what they could. “It’s not a good environment for kids being packed together,” said Nithya. “I don’t mind a few days here and there but we are now forced to uproot for months each year.”

Windmills, the people believe, are one reason for the severe flooding since 2022. To build the 30 Thambapavani turbines, an elevated access road stretching twenty kilometres was constructed, allegedly, without proper drainage. Moreover, ironically to protect trees, cables were laid in underground trenches, rather than using the typical overhead pylons.

But windmills aren’t the sole culprit. Nithya pointed out that culverts were blocked by shrubbery. Natural drainage paths were also distorted by levelling the land for agriculture. Khadija Umma [name changed] said that besides the windmill roads, the government also built roads into her rural village of Kadaspathri, again without proper drainage. Further, at least four thousand holes were dug deep for the exploration of mineral sands. Unusually heavy rains, possibly as a result of climate change, further exacerbate the problem.

An ecological conflict zone

Mannar island has some of the lowest lying areas in Sri Lanka, with several points being at or below sea level. It is very sensitive to change. But man made changes — from large scale wind projects to village-level farming — aren’t done according to a master plan, paying little regard to cumulative impacts. Nature reserves, tourism sites, bird migration paths, windmill projects, and sand mining exploration regularly overlap on the same lands.

On 13th August, after meeting with protestors, President Anura Kumara Dissanayake announced a month’s suspension on windmill construction.