Last week, Ananda Wijepala, the public security minister, bypassed established press regulation mechanisms to lodge a complaint with the Criminal Investigation Division (CID) over a controversial news report.

The move — denounced as press intimidation by the media fraternity — resulted in the CID summoning Mahinda Illeperuma, editor-in-chief of the Sinhala daily Aruna.

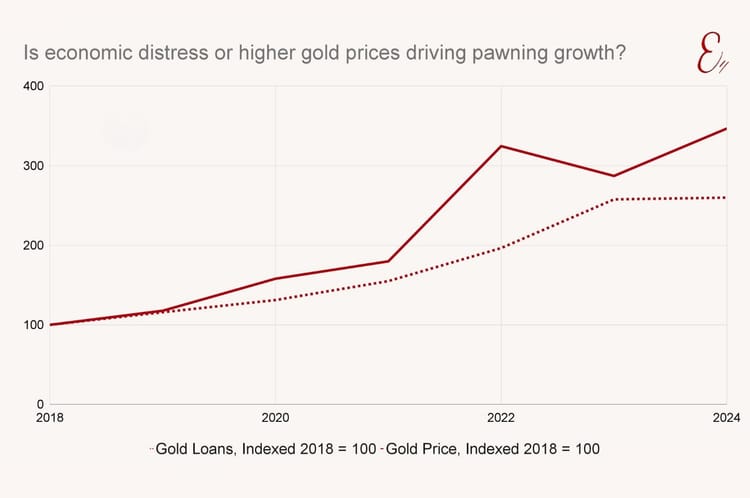

The controversy stems from an Aruna story, published last Wednesday, 19 November. It claimed that the police now require clearance certificates to be approved by local public security committee heads.

The Aruna story immediately drew public attention and provoked a heated exchange in parliament. Sajith Premadasa, the opposition leader, accused the government of creating a “police state.”

But Wijepala rejected the article and threatened to call the newspaper editor before the parliamentary privileges committee. Police called the news “false”, clarifying that approval from the committees is not needed for clearance certificates.

Ignoring established process

Media veterans criticise the government’s failure to use existing self-regulation mechanisms prior to launching the CID investigation.

Illeperuma says that Wijepala didn’t exercise his right-of-reply in the Aruna, and that the paper published Wijepala’s rejection in parliament. Nor did Wijepala complain to the press complaint commission or press council, confirm the heads of these institutions. There is also the option of a civil defamation suit.

“The government collectively decided this is serious misinformation, so we needed to take action. There is a record of the same newspaper publishing fake news,” said Kaushalya Ariyarathne, deputy media minister, adding that this was why Wijepala skipped the press complaint commission and press council.

“You can criticise the government but you cannot spread fake news,” the deputy minister added.

Siri Ranasinghe, Lankadeepa’s first editor, condemned the government’s move.

“This could have been resolved by the press complaint commission. He hasn't murdered anyone, has he? This is not something that warrants bringing in the police. This is intimidation, and is like a shadow creeping over the media.”

Industry associations are up in arms about the CID complaint. The Sri Lanka Working Journalists Association, the Free Media Movement, and the Federation of Media Employees Trade Union all condemned the summons and called it intimidation.

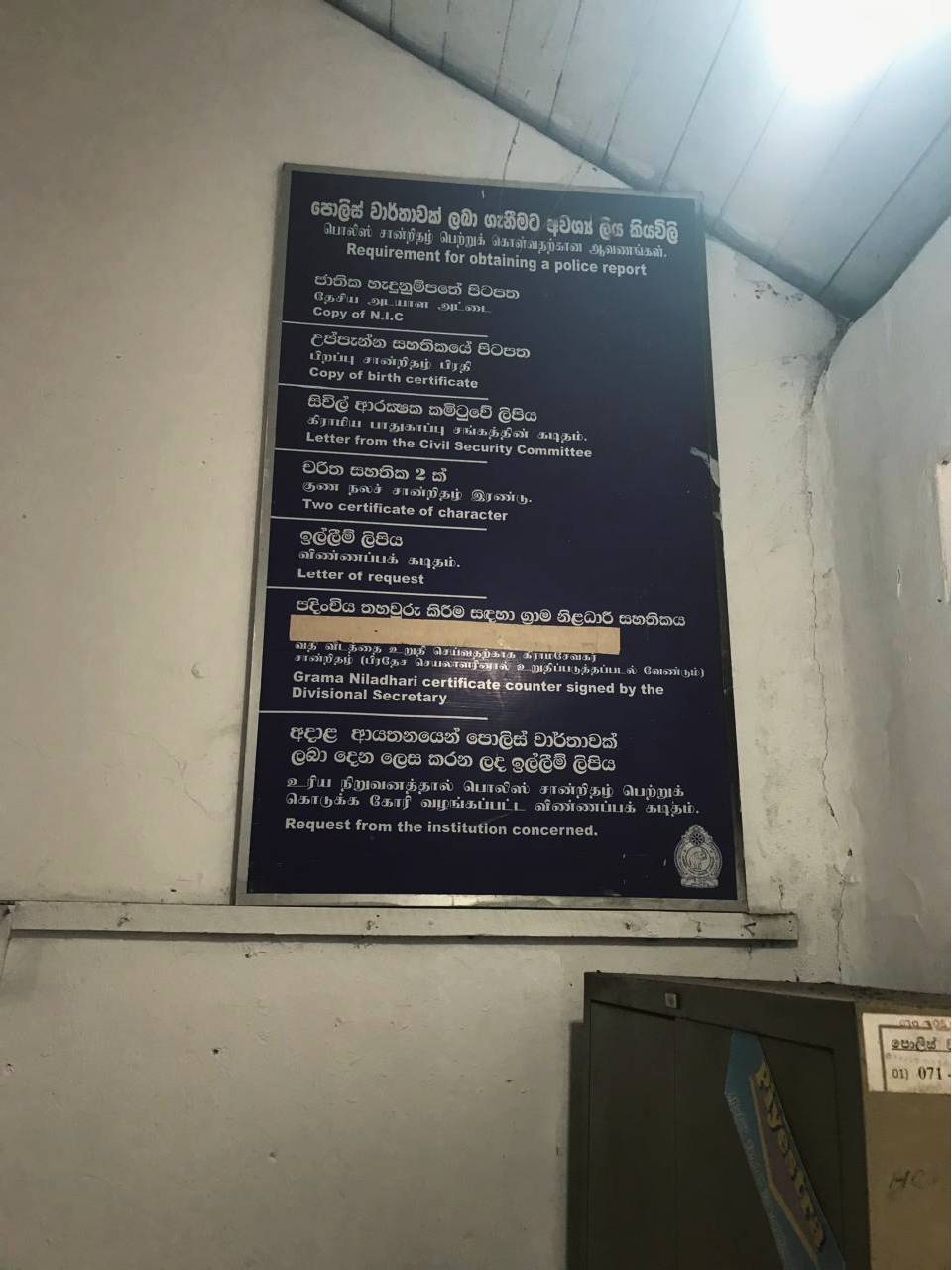

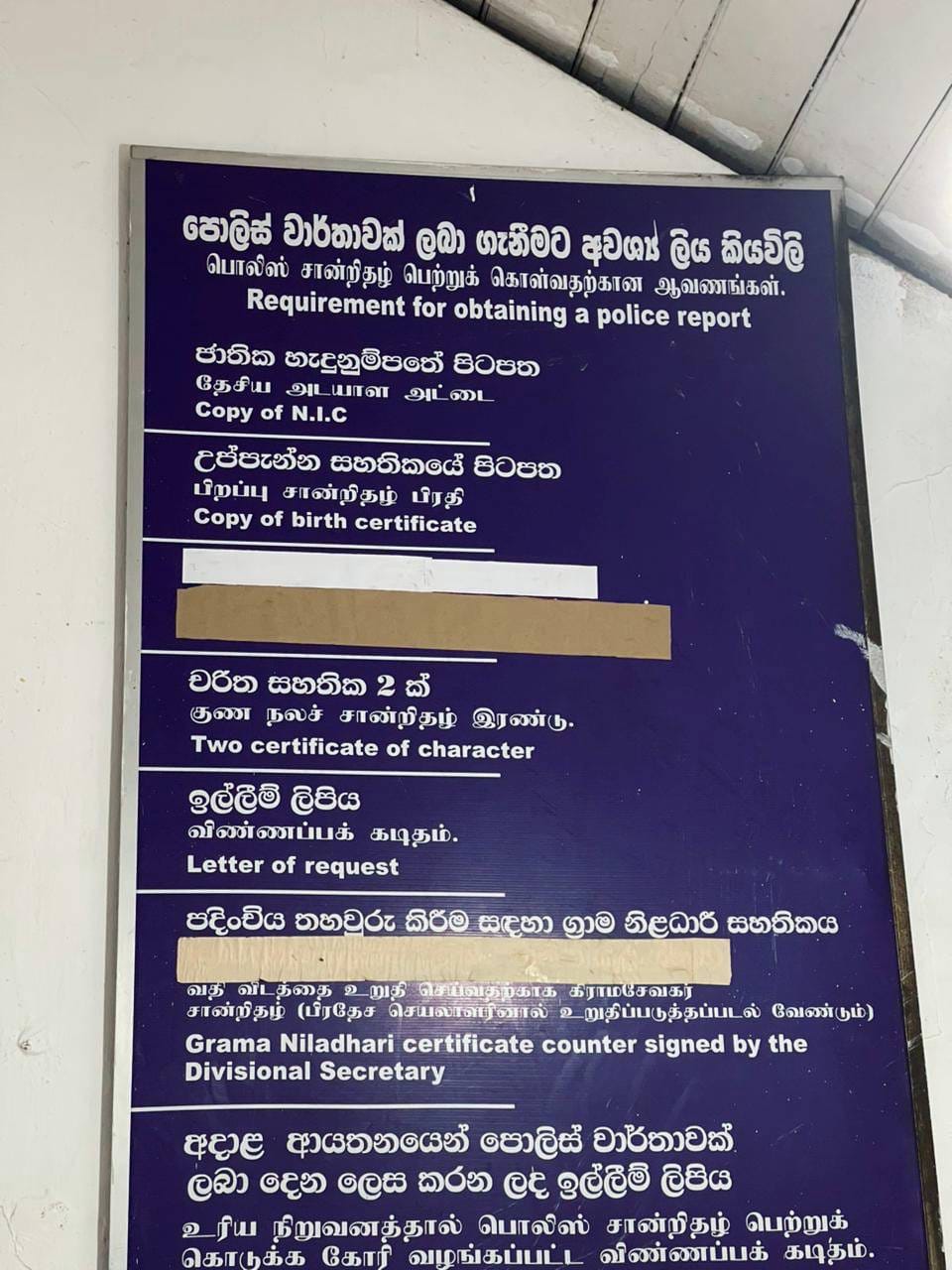

Notice at the Baddegama police station. The requirement for a "letter from the civil security committee" has now been covered. Photos: SJB

The typically restrained Editors’ Guild also said the incident was “very serious.” Mohanlal Piyadasa, the guild’s secretary, said this was the third time Illeperuma had been summoned to the CID since the current administration came into power.

Duminda Sampath, working journalists association president, said that while past governments used physical violence and harassment, the current government is increasingly relying on the police to persecute the press.

Illeperuma informed the CID he was sick and did not adhere to the summons — a choice cheered on by journalists and media activists.

The crux of Wijepala’s escalation to the CID lies in the veracity of the Aruna report. The CID said the summons was issued “regarding the false news item disseminated in the Aruna newspaper”. They effectively declared the claim untrue before any formal investigation commenced.

The Examiner conducted its own inquiry into the central claim: that police clearance certificates now mandate a letter of approval from the local public security committee.

Officially, a police clearance certificate is solely intended to confirm an applicant’s criminal record — specifically, convictions in Sri Lanka. The applicant’s subjective moral character is, by definition, outside the scope of the clearance.

But, the ground reality presents a more nuanced and inconsistent picture. We contacted six separate police stations.They uniformly confirmed that a formal letter of approval from the public security committee is not a requirement for an application. This official line aligns with the clarification issued on the police website.

Yet, a substantial body of evidence confirms that the Aruna report captured a localised reality. The police clearance division, attached to the administration headquarters, acknowledged that the issuance process often involves a “local inquiry by the police, which can include a character verification component.”

A grama niladari from the Central Province and a Northern Province pradeshya sabha member both confirmed, on the condition of anonymity, that police routinely approach these public security committees to informally ascertain an applicant’s character. This practice is long-standing and informal, but it underscores the reliance police place on these local bodies.

Attached to grama niladharis, public security committees have existed in various forms for years. Occasionally, they’ve been referred to as civil security committees.

The grama niladari further worries about politicisation in recent months. “The police requested me to appoint certain people supportive of the NPP government. I’ve been a grama niladhari for 26 years. This is the first time I’ve been asked to do this.”

The most compelling evidence supporting the story’s premise surfaced in two locations. The first was at the Baddegama police station, where Opposition Leader Premadasa tabled a photograph of a notice board clearly listing the “Civil Security Committee” letter as a requirement for clearance.

Though Baddegama police later informed us the rule was no longer in force, they could not confirm when it was abandoned.

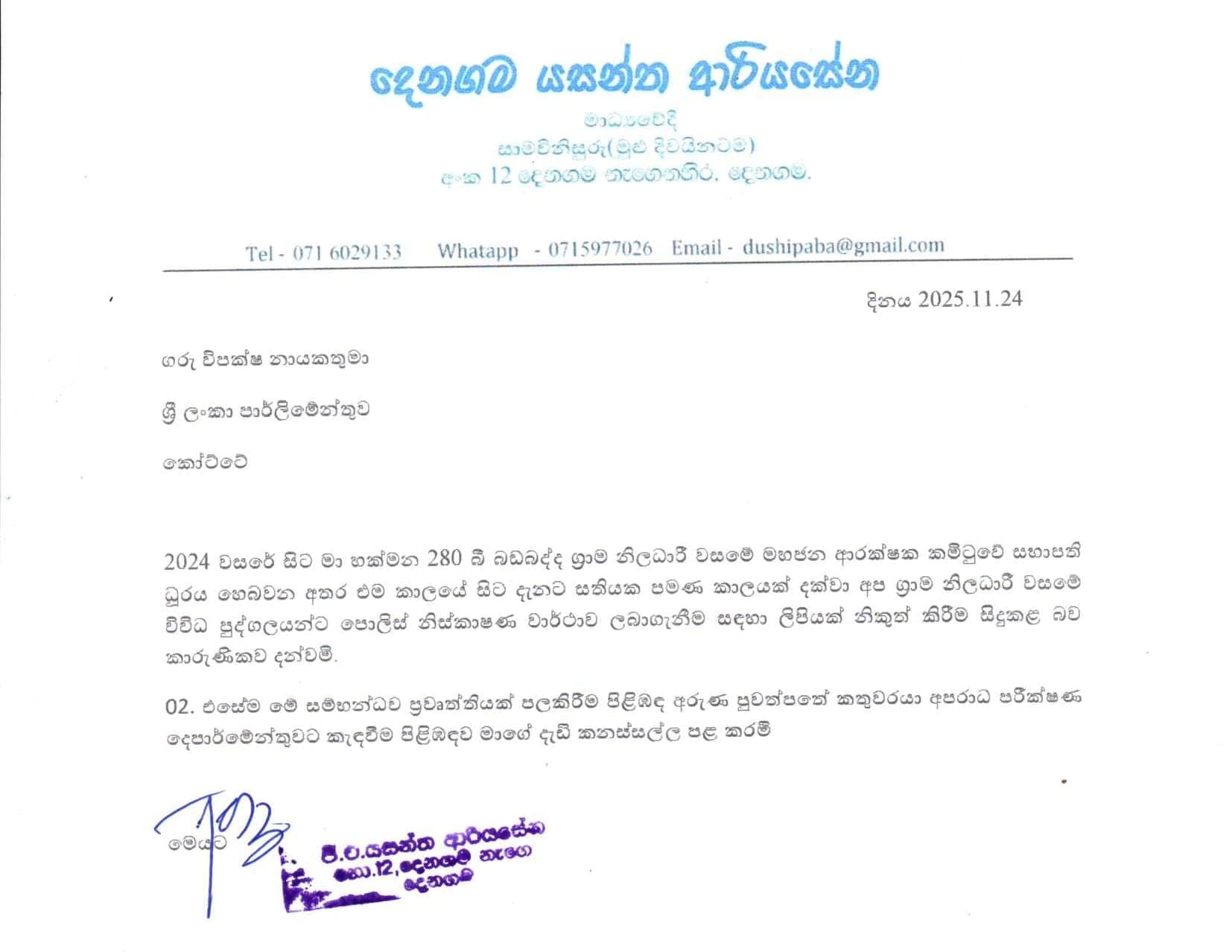

The second was the testimony of Yasantha Arthayasena, the chairman of the Hakmana public security committee. He confirmed to The Examiner that he has been issuing such letters since January 2024. Crucially, he noted these requests originate from the applicants themselves, not from police headquarters, making it ambiguous whether it is a mandatory police requirement or merely a document perceived as necessary by the public.

In short, The Examiner’s investigation finds that there is a practice of obtaining character verifications from public security committees in some parts of the island, but it doesn’t appear to be a formal, island-wide policy.

Aruna’s failure to list its sources allowed the government to dismiss the entire issue as "misinformation". Nalinda Jayatissa, cabinet spokesperson, ridiculed the opposition's evidence, equating the article’s sources to “tomato sauce.”

Self-regulation vs state control

This week’s dispute between the media industry and the government underscores a broader, ongoing debate between self-regulation and state regulation of the media.