For all the posturing and negotiating in the Alps, the island’s progress on human rights, accountability, and justice is slow and halting. Political parties from both the north and south acknowledge that core issues of justice and accountability remain unaddressed.

Foreign Minister Vijitha Herath’s statement on Monday offered yet more promises. He committed to repeal and replace the PTA and amend the Online Safety Act. He also highlighted the government releasing northern lands and reopening roads since coming into power last year.

But the Council is unlikely to be convinced that Sri Lanka should be removed from the agenda. Especially as Herath rejected any “external mechanism”, including the UN’s Sri Lanka Accountability Project, an evidence gathering mechanism.

The draft resolution calls for an extension of the UN’s monitoring mandate. The Examiner learns that Sri Lanka is unlikely to ask for a vote, in which case it will pass automatically, keeping Sri Lanka on the Council’s agenda till 2027.

Despite core issues remaining unaddressed, many feel the UNHRC does matter. The missing persons office, reparations office, and enforced disappearances act are direct outcomes of sustained Council scrutiny.

Mahesh Katulanda, the missing person’s office chairman, said initial investigations into cases that occurred between 2000 and 2009 had been completed. From the nearly 6700 inquiries, the office had recommended 1700 cases for “advanced investigation” based on suspicions that the concerned individuals had been forcibly disappeared .

Evidence today, justice tomorrow

Bhavani Fonseka, a researcher at the Centre for Policy Alternatives, argues the UNHRC’s wheels of justice turn not just for today, but also for tomorrow.

The Accountability Project — which began investigations into human rights violations in 2021 — now holds over 105,000 pieces of evidence in its repository.

Fonseka said the project plays the role of “preserving evidence” for future trials. “That wouldn’t have been possible without the UNHRC resolution.”

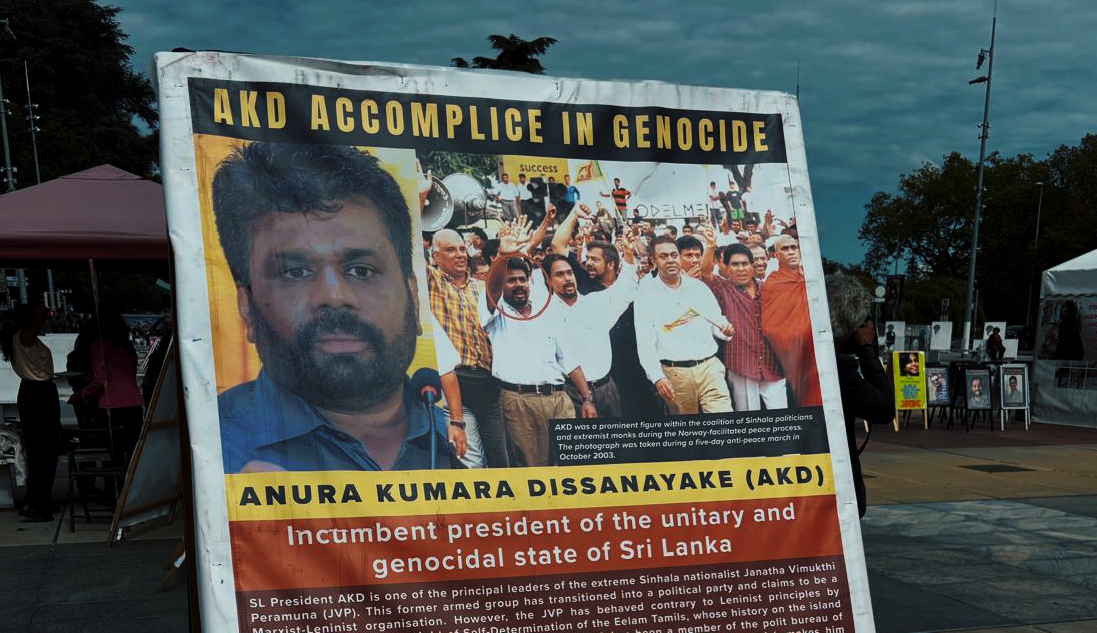

The project covers a wide range of crimes, not limited to war time atrocities committed by the government and LTTE. It also collects evidence on JVP-era enforced disappearances and ongoing violations. But successive Sri Lankan governments, including the current JVP-led one, have rejected the Accountability Project saying it will “create division” and “jeopardise” national processes. There is no indication that the Sri Lankan government has requested evidence from the project for use in domestic investigations.

Other countries have. The accountability project has received requests for information on eleven named individuals from foreign authorities. So far, however, no accused Sri Lankan war criminal has been prosecuted by a foreign country under universal jurisdiction. If the resolution on Sri Lanka is to pass in the next few weeks, the Accountability Project will continue its work. Likely, it will switch gears from collecting evidence to creating case files on accused individuals and encouraging their use by member countries.

The ICC mirage?

“You can’t expect criminals to deliver justice,” said Leeladevi Anandanadarajah of the Association of Relatives of Enforced Disappearances who is still looking for her son.

Anandanadarajah is calling for trial at the ICC, an international tribunal based out of the Netherlands. She knows it’s almost impossible given that there are only two ways the ICC will take on a case: by Sri Lanka being a signatory to the Rome Statute, which it isn’t, or by referral from the UN Security Council. Russia and China, who have opposed resolutions on Sri Lanka, have a veto at the Security Council.

“We have to at least try once,” said Anandanadarajah, who is rallying support to go to the Security Council.

Tamil parties, victims’ families, and the diaspora consistently push for international investigations and trials. But all major national political parties in the south are opposed. The SJB has no objections to international expertise at the investigation level but will not support it in the judicial process. “The community has lost faith,” says Harsha de Silva MP. “The way to re-establish that is through a domestic mechanism that is independently carried out.” The SLPP has consistently taken a strong anti-UNHRC stance, dismissing appeals to the international community as attempts to “tarnish” Sri Lanka’s image.

UNHRC’s link to GSP+

The UNHRC isn’t just about international trials. Activists also see it as a way to keep Sri Lanka on its toes. “The UNHRC is very important because it’s the only accountability mandate we have at the moment,” said Anushani Alagarajah of Adayaalam, a Jaffna-based think tank.

“The Sri Lankan government only talks about this when there’s an EU delegation visiting or GSP+ review or a UNHRC session.”

Historically UNHRC resolutions have materially influenced Sri Lanka’s bilateral relationships...