The Examiner has more opinions than it has staff. We maintain unanimity in our facts, not the inferences we draw from them. This examination is no exception.

When Chamari’s period arrives, her lottery booth becomes a changing room. The only toilet accessible in her part of Boralesgamuwa is a 20 minute walk away, inside a temple. She can’t use it when she’s menstruating.

“I change my pad inside the booth. When I’m not on my periods, I have to walk quite a distance to the temple bathroom, so I only go twice a day,” says Chamari Prabodani, a 36-year-old who has been working as a ticket seller for two and a half years.

There’s only one public toilet within the Boralesgamuwa Urban Council limits. Prabodani, like thousands of other women, plays an essential role in Colombo’s economy. Yet, the question of infrastructure remains: is Colombo able to facilitate the mobility of women as they work?

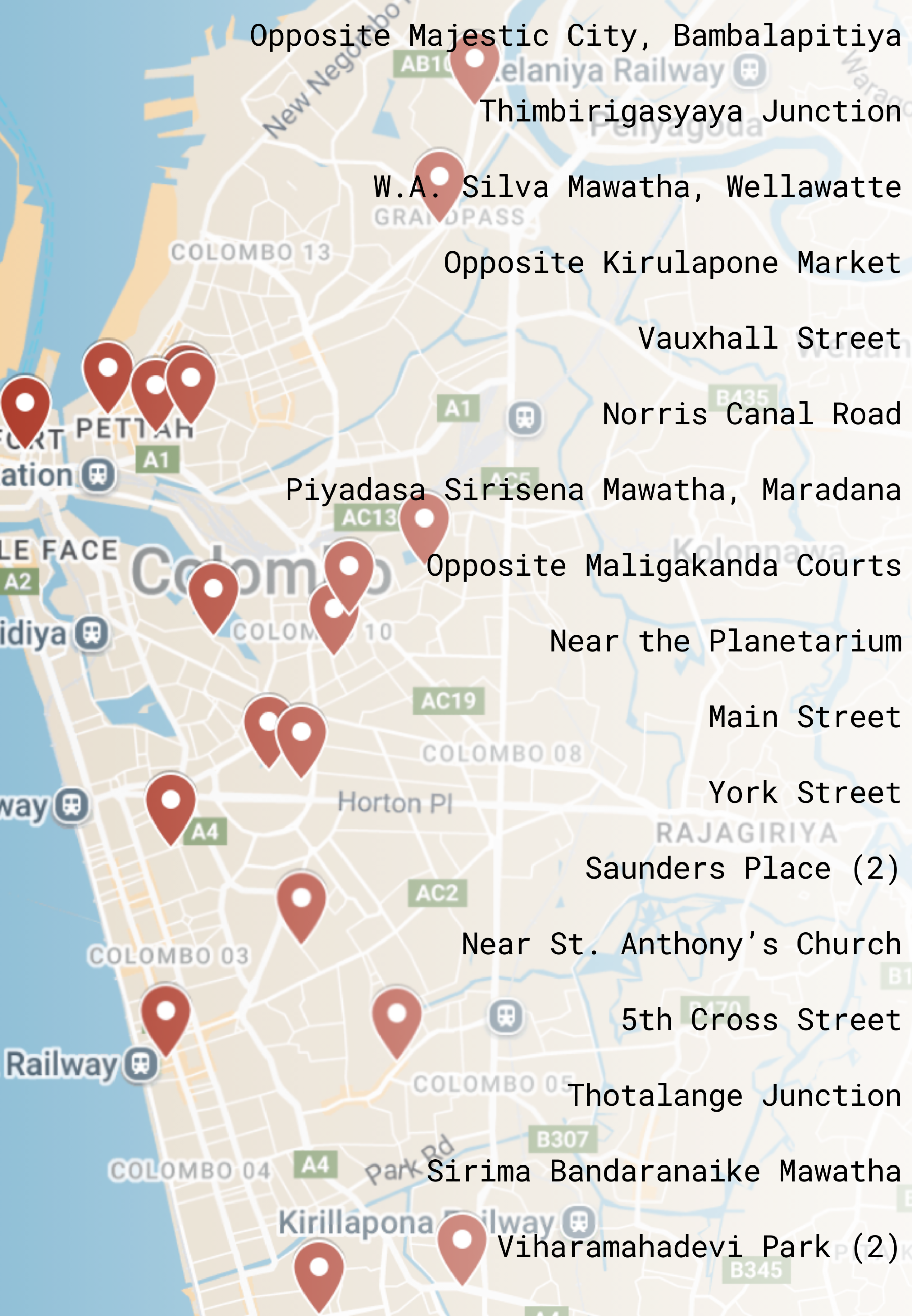

Approximately seven lakh people enter the city every day. But, according to the CMC, there are only nineteen municipal toilets in the city. That’s less than three toilets per one lakh people. Tokyo sets a benchmark at about 50 public toilets per lakh people.

No man’s problem

No single government agency is directly responsible for addressing the sanitation needs of Colombo’s floating population. The UDA and the municipal council both have roles to play, but neither takes full responsibility.

The UDA draws up a “high-level” plan by naming zones like bus halts, public markets, shopping complexes, and housing schemes. “But we don’t write about public toilets separately in our plans as they would be too detailed then,” says UDA Chair Kumudu Lal.

This approach to urban planning deviates from global recommendations for designing gender-inclusive public spaces. For instance, the World Bank proposes abandoning typical zoning practices as they reflect traditional gender roles and divisions of labour.

Local authorities are mandated to promote public health and sanitation services but Anuja Mendis, in charge of city planning at the CMC, attributes the lack of toilets to poor planning. The UDA’s city plans weren’t “people-centric”, he says.

“Colombo is currently being developed under the 2022-2031 plan, which doesn’t even suggest locations for the construction of new public toilets.”

Outside the plan, the CMC identified the need for new toilets in Pettah, Borella, and Narahenpita. But they have not been built: the CMC is stuck finding land for their construction.

“If the UDA’s development strategy identified specific locations for the construction of new toilets, then land could have been allocated,” says Mendis.

We examined the development plan of eight local authorities in the Colombo District. From these, the Dehiwala-Mount Lavinia one stands out for explicitly stating that public sanitary facilities are “important” for an area with frequent population flow. It proposes nodes for public toilets, including at all major public transport hubs and other public spaces like parks. It also recommends features like disability access, baby-changing facilities, and even displaying direction maps for easy identification.

For all the ambition, execution remains slow. Four years after the Dehiwala-Mount Lavinia plan was drawn-up, only three public toilets are available for the 21 square kilometer area. Two more are waiting to be developed.

A man’s city

Colombo Urban Lab researcher Meghal Perera says that Sri Lankan town planners usually imagine cities for able-bodied, middle-aged men.

“Take conversations about transport for instance, which don’t consider the kind of dynamic journeys that women take to pick children up from school or run errands throughout the day. Instead, we only think of transport as being for those commuting to work and back home. Similarly, in the conversation surrounding public toilets, there’s an assumption that women are staying at home and not really engaging in the public sphere,” says Perera.

Although there are plans to upgrade urban transport infrastructure, like the Kelani Valley Line’s upgrade to run regular services throughout the day — not just at rush hour — they’re yet to be implemented.

When city planning fails to account for women workers, Perera believes their geography is “shortened”. Informal vendors have to work close to their homes, rather than where they could earn more.