The Examiner has more opinions than it has staff. We maintain unanimity in our facts, not the inferences we draw from them. This examination is no exception.

If you want to get rich, build a [rail]road first” — Chinese proverb

Every day, over one and a half lakh passengers commute along the High Level Road. Their journeys are long and arduous. The traffic is fierce. Hot, overcrowded buses sit in a cloud of pollution. Personal space is non-existent, harassment flourishes. Those in cars are lucky. Yet they too suffer long commute times into the city — often longer than an hour from Kottawa.

The road’s maelstrom makes the silence of the railway track more stark. Especially as the Kelani Valley train line runs right next to it. A small fraction of the road traffic — less than 20,000 commuters — use the railway.

Demand is not the problem. The eight trains chugging into Colombo every morning are packed. As are the eight that return towards Avissawella in the evening. They stop in the bustling satellite towns of Nugegoda, Maharagama, Kottawa and Homagama. If more trains ran, they too would be full.

But just buying more trains won’t work. The Kelani Valley Line has a single track, meaning trains can’t simultaneously run in both directions. Without double tracking, more trains will be of little use.

The line also crosses many major roads. Should the number of trains increase, road crossings will be closed for longer, bringing road traffic to a standstill. Engineers have many solutions for these problems, though they don’t always agree on which solution works best. As these debates raged, the promise of shorter, pleasanter commutes was shattered.

Battle of the engineers

In 2015 the Yahapalanaya government set out to modernise the railways. But two opposing camps among engineers disagreed on the details.

The Institution of Engineers, Sri Lanka’s engineering association, had long advocated for railway modernisation. They recommended starting with the Veyangoda-Panadura corridor as it carries over half of all rail traffic, upgrading it through electrification.

But other engineers, including Dimantha de Silva, disagreed. They argued that choosing the first line to modernise based on existing railway traffic didn’t make sense. Instead, they wanted to upgrade the Kelani Valley line to fill a major gap in Colombo’s rail network: no east-west connections. They would do this through double-tracking and elevating the line.

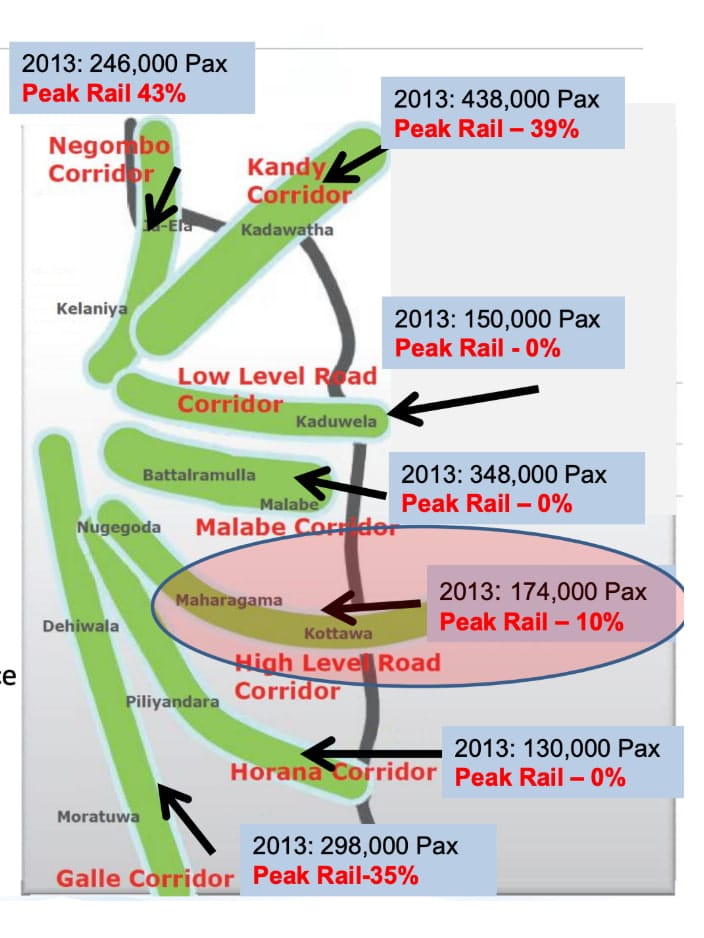

Colombo lacks meaningful rail connections with all suburbs along the Kadawatha to Horana arc. Malabe, Athurugiriya, Homagama, Kottawa, and Kaduwela, some of the fastest growing neighbourhoods, are not connected and commuters travel almost exclusively by road.

By contrast, along the north-south axis from Panadura to Veyangoda, rail carries a third of all passengers. During peak hours, trains run almost every ten minutes on that corridor.

Unsurprisingly, five times as many commuters take the train from the Moratuwa area compared to from the Kottawa area. If not for the railways, Galle Road would have been in gridlock years ago.

The question of which railway line to prioritise was not an easy one to settle. But the government finally sided with the Kelani Valley line proponents, and the project was born.

Victorian era to modern day

Thus the Kelani Valley line became the vanguard of Sri Lanka’s railway modernisation. The plan introduced a series of firsts: electrification, elevation, automated ticketing, and air-conditioned commuter trains. It aimed to pull the railways out of the Victorian era and into the present, thereby solving one of Sri Lanka’s biggest economic constraints: long travel times and limited urbanisation.

The Asian Development Bank too was of the same mind. Without better public transport, the bank understood that Colombo’s growth would be killed by congestion. In 2019, it financed detailed feasibility studies for every railway line into Colombo. The Kelani Valley Line study recommended double-tracking for higher train frequency. It also called for elevating the line above road traffic, to eliminate the disruptions that come with railway-road crossings, especially in light of higher train frequency.