The Examiner has more opinions than it has staff. We maintain unanimity in our facts, not the inferences we draw from them. This examination is no exception.

The year is 1988. Lunch is served. Between beef curry and talk of insurgency, J.R. Jayewardene, preparing for a leisurely retirement studying Shakespeare, parries the sharp tongues of his own kin. It is, after all, a family lunch. The Geneva Conventions, often observed in the breach on our island, are suspended altogether.

The company is bewildered and confused. The certainties of yesteryear have given way to the chaos of the present. The old order — hierarchical, unequal, and unjust; yet broadly rules-based and predictable — has yielded to the politics of the pogrom, the democracy of the tyre necklace, the justice of the Black Cat, and the cultural triumph of library burning. Their kinsman’s Lanka offends their gentler, genteeler sensibilities.

Having tasted the fruit before it planted the tree and sown the winds of racism, Sri Lanka is harvesting the whirlwind of insurgency. The state makes alliance with the street to answer violence with violence. In league with the underworld, it acquires a criminality and a cruelty not seen since the Dutch.

Irritated by his relatives’ sniping at the lunch table, J.R. breaks his calm. In his grave, gravelly voice he exclaims, “This is Sri Lanka. This is not Switzerland. The strong men will always rule this country. I am doing this for you, if you cannot bear what must be done to protect civilisation, then go back to Montreux!”

The remark is revealing. His was a politics where ends justified means; in which the promised land of a Switzerland of the East excused almost everything.

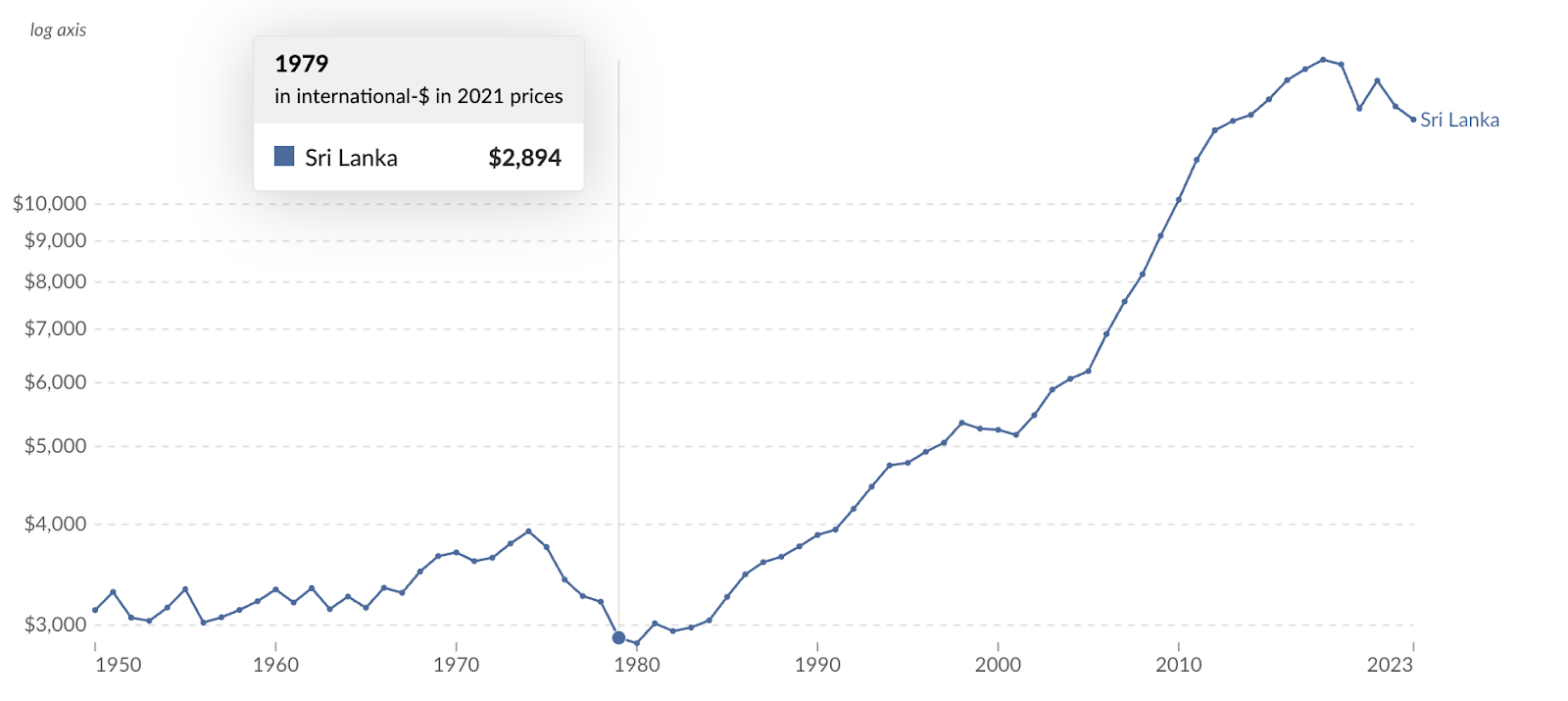

For a time, the economics vindicated him. Until 1977, even as the population grew, people didn’t grow poorer. But they didn’t grow richer either.

After J.R.’s liberalisation in 1977, economic growth outpaced population growth. Sri Lankans grew visibly richer. Export industries flourished. Ports, tourism, and remittances joined garments in supplying the foreign exchange that had been long in deficit. For once the island kept pace with its Asian peers.

This was not an accident. J.R. had studied hard in opposition, served long as finance minister in past governments, and knew what had to be done.

His handpicked lieutenants — Lalith Athulathmudali, Ronnie de Mel, Upali Wijewardene, R. Premadasa, Gamini Dissanayake, and Ranil Wickremesinghe — were a front bench that is yet to be surpassed. They established the institutions which propel our economy to this day: the Board of Investment, then known as the Greater Colombo Economic Commission, the Urban Development Authority, the free-trade zones, the ports authority, the development banks, and a host of other agencies modelled, often quite explicitly, on Singapore.

Let the robber barons come

The sea-change in economic ideas and policy cannot be overstated. Sri Lanka went from one of the most closed and dirigiste countries in Asia to one of the most open. We were the first South Asian country to liberalise, well over a decade ahead of India.

During J.R.’s time as president, the island’s economy grew thrice as fast as it did between 1970 and 1977, even when adjusting for inflation. Though inequality increased, the typical household’s income grew by over one and a half times during his tenure. And it grew in dollar, not rupee, terms.

He adroitly managed the dynamics of his ambitious liberalisation programme, securing vast sums of foreign aid. In 1980, Sri Lanka enjoyed the world’s highest foreign aid per capita in the world. He also marketed a formidable pipeline of development projects.

Yet the economic revolution was stillborn. Instead of agrarian reform of the East Asian sort, the government poured foreign funds into dry-zone irrigation. The Mahaweli scheme reduced the cost of electricity vital for industrialisation. But it still prioritised low-productivity agriculture over high-productivity industry, precluding the structural transformation that drags countries out of poverty.

Economists argue the massive foreign currency aid for Mahaweli also led to currency overvaluation, dampening Sri Lanka’s export competitiveness.

And aid enabled cronyism. Mahaweli became the OG training school for tenderpreneur robber barons. White elephants like Air Lanka were also birthed against better advice, and duly became a drag.

Mahaweli, funded both through aid and debt, crowded out the private sector. J.R. asked Goh Keng Swee, Singapore’s First Deputy Prime Minister and a key architect of its meteoric economic rise, to write a report on the economy in 1980. The report highlighted a striking figure: government investment accounted for 85 percent in Lanka, far outweighing the private sector.

In Singapore that number was 25 percent. By the late 1980s, when J.R. left office, Sri Lanka’s debt-to-GDP ratio reached unsustainable levels, breaching 100 percent.

Bad politics is bad economics

If the policies were flawed, the politics was fatal. When he left office in 1989, Sri Lanka was fighting for its very life. The island was ablaze with insurgency in the North, insurrection in the South, and Indian troops on the ground for the first time in centuries (the Indian gurkhas sent to guard Katunayake during the first JVP insurrection don’t really count) .

His political violence thwarted his economic renaissance. In 1983, a semiconductor plant was under construction at Katunayake. Sri Lanka was on the verge of developing Asian Tiger style electronics exports —- the magic that drove countries from third world to first.

After Black July, the American semiconductor firms decamped to Penang, which became Southeast Asia’s Silicon Valley.

Similarly, just before Black July, a group of Japanese companies — including Sony, Sanyo, Marubeni, and the Bank of Tokyo — arrived in the country after months of courting. But when Chandi Chanmugam, deputy treasury secretary and the government’s foreign investment committee chair, was about to deliver the keynote at a conference held for the visiting businessmen, he received news of the murderous gangs roaming Colombo.

He delivered his speech. He promoted Sri Lanka as an investment destination. Then he left immediately after, fearing for his daughter’s life and worrying that his house neighbouring the prime minister’s office was about to be burnt down.

The investors packed their bags the next day and returned to Japan. The Japanese investment that transformed Southeast Asia passed us by.

Sri Lanka’s exports, with the exception of services exports, are structurally where they were in June 1983. Our main manufacturing exports remain apparel and solid tyres. The exodus of talent that followed Black July has never ceased.

The state was also saddled with the economic costs of the civil war that ensued from Black July. When J.R. assumed office, defence expenditure was 0.8 percent of GDP. By the time he left, it was generally more than double that.

Deformed character

Less than a fortnight before the bloodbath of Black July, J.R. said: “I am not worried about the opinion of the Jaffna people now. Now we can’t think of them. Not about their lives or their opinion about us.”

While thousands of citizens were killed, he did nothing. Nor could he be seen or found. After the riots ended, his statement to the country was: “I will fulfill Sinhala aspirations. I will not allow the country to be divided."