The Examiner has more opinions than it has staff. We maintain unanimity in our facts, not the inferences we draw from them. This examination is no exception.

“Will AI replace lawyers?” asks the moderator of an AI panel at the Junior National Law Conference. “No!” the young lawyers in the room shout back.

The conference, held in November last year, was trying to encourage AI adoption. But, many lawyers are anxious about AI, fearing punishment from seniors for using it, or worse, machines taking their jobs.

Anxieties and embarrassment about AI are preventing honest conversations about its use. But lawyers are using the technology anyway. And judges too are following suit.

Judges and AI

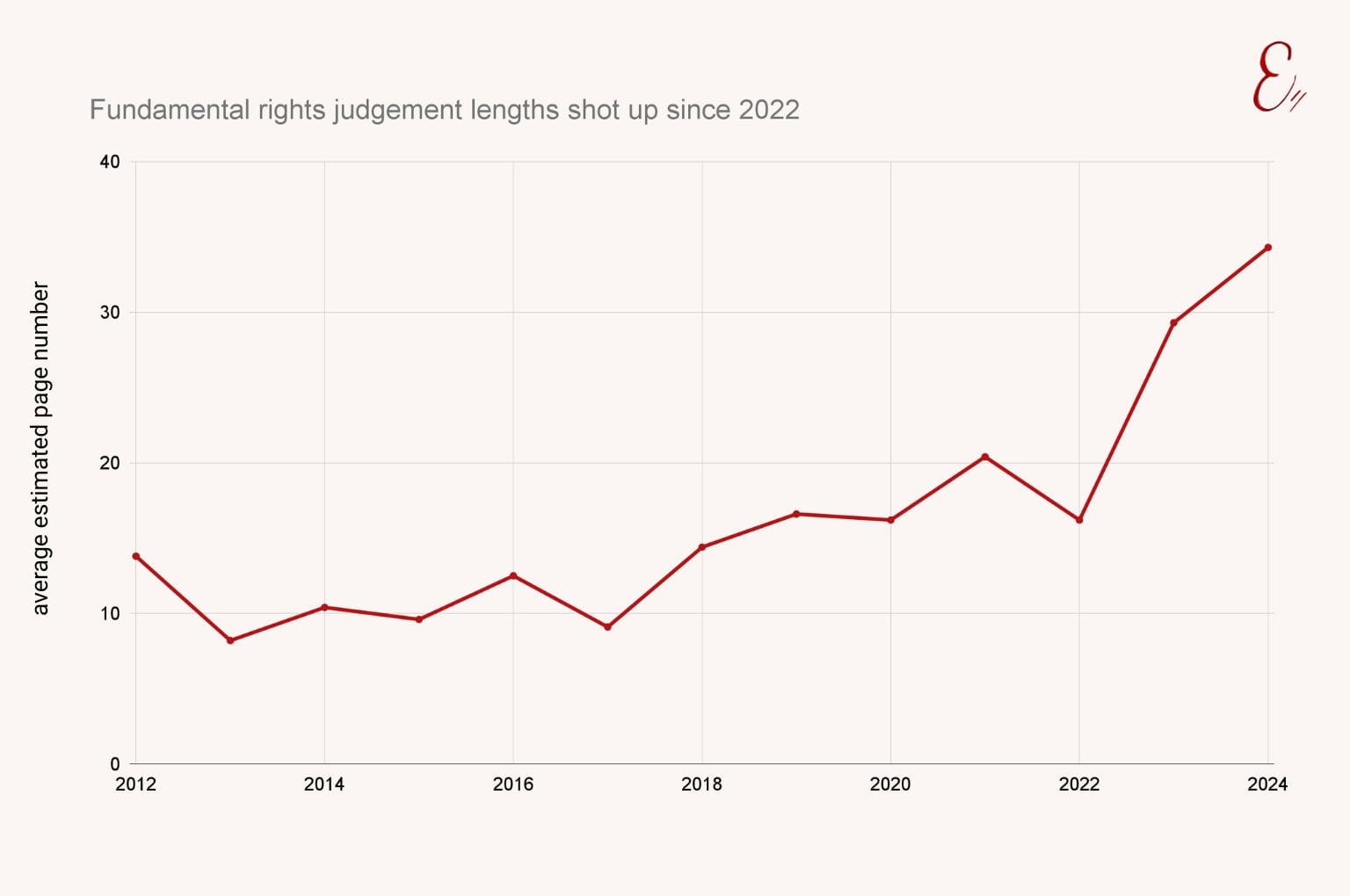

Judgements increasingly contain Americanised legal terms like lawsuit and subpoena. Since 2022, the year ChatGPT was released, available data suggests that Supreme Court and Court of Appeal judgements have lengthened. For instance, the length of judgements for fundamental rights cases has nearly doubled.

Ai Pazz, a Sri Lankan legal AI company, confirm judges are using their platforms.

Since Sri Lanka largely operates on common law principles, finding judicial precedents is an important aspect of judges’ work. Even though local precedents can be more important, international precedents are often easier to find, simply because they are more searchable. In the past, those working in law had to trawl through physical libraries or search using exact phrases on Law Lanka.

Many judges are quite old, so they may not be using AI themselves. But in the higher courts they rely on their research assistants; usually law graduates just out of university. Many of them are active users of paralegal.lk, a legal AI company.

“Using AI for legal research makes a lot of sense, but the problem arises if AI is used to draft judgements,” says Elijah Hoole, paralegal.lk's founder. “Because language is very important in law, getting AI to draft a judgement also effectively outsources the human role we want judges to play: using their discretion and grappling with an issue.”

As Sri Lanka mostly follows the common law tradition, law also comes into existence through judicial precedent. If a judgement is written today with the help of AI, it effectively becomes law in the future.

Despite the high stakes, the Judicial Service Commission is yet to create an AI policy for judges. But, conversations have started. Last year, the UNDP held AI sessions for judges including training on how to use it without “dulling judicial reasoning.”

Lawyers and AI

Sanjeewa Fernando, the appeal court’s registrar, is observing more American language in lawyers’ submissions. “I’ve seen ‘subpoena’ being used a lot more for example,” he said, “this is very unusual because in Sri Lanka we use ‘summons’.”

Conversations are also opening up among lawyers. The AI session at the Junior National Law Conference was the first of its kind in Sri Lanka.

Ruven Weerasinghe, a lawyer, is optimistic. “It’s like having a junior who does the first draft. And then I do edits and review it,” he said.

Weerasinghe isn’t too worried that AI will replace junior lawyers as Sri Lanka lays claims to a huge case backlog. “Currently just a handful of lawyers do all the work. But AI makes us more efficient. It allows junior lawyers to be able to handle more complex cases.”

Most lawyers are still using generic AI tools like ChatGPT. At the law conference, the moderator asks over fifty lawyers in the room if they use ChatGPT. About a third of them raise their hands. Asked if they use Gemini, Grok, Claude, or specialised legal AI, far fewer hands shoot up.

But it is easy for lawyers to misuse generic AI. If lawyers insert sensitive case information into ChatGPT, they risk sharing confidential information. In August last year, thousands of ChatGPT chats were leaked online. ChatGPT also retrains its model with user data.

Generic AI also suffers from extensive hallucination. In May 2025 alone, courts around the world found nearly 120 instances of hallucinated AI. The primary culprits were lawyers, but some were judges too. At the Junior National Law Conference, speakers urged lawyers to review work before submission. “You are ultimately liable,” they said.

To tackle hallucination and privacy issues, engineers are building specialised legal AI. But Thanuki Goonesinghe, a tech lawyer, is skeptical about the effectiveness of legal AI models like Harvey AI in a Sri Lankan context.

“They aren’t trained on data from Sri Lankan statutes, case law, or regulatory practice. So even if they generate an answer, it may not be accurate or contextually relevant. And because they are specialised they won’t do a general Google search either,” she said.