The Examiner has more opinions than it has staff. We maintain unanimity in our facts, not the inferences we draw from them. This examination is no exception.

Two failed insurgencies against the state left the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna in the electoral wilderness for decades. In 2019 the National People’s Power, NPP, was created, and it functions as the parliamentary front for the older Marxist party. The JVP-NPP, both led by current President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, quickly became a strong voice for justice in the opposition.

In the past decade, Anura sahodaraya led only a handful of party members in parliament. But he raised his voice about everything. From exposing corruption to exposing torture, he was known for standing on the people’s side. His presidential campaign reflected this focus, and the final rally at Nugegoda before the 2024 presidential election captured an energy for simmering change.

Hope was high as the massive crowd waited for their revolutionary-turned-politician. The crowd hung on to every word when he delivered a speech full of promises grounded in the everyday struggles of people.

A month after winning the top post, he cemented his position by obtaining a supermajority in parliament with a direct mandate from the island’s North in tow. The NPP was the first Southern party in the country’s nearly 100-year electoral history to obtain such a resounding mandate from the North.

The supermajority, formed entirely of NPP members, allows the government to pass any law without support from other parties — a rare opportunity for those eagerly awaiting long-contested reforms.

Today, President Dissanayake leads 159 members in parliament. But in the year since gaining power, the JVP-NPP government’s legal reform programme to ensure “civil rights of all” has been decidedly less dramatic than its loud and romantic promises when in opposition.

News of long-awaited rights-based law reforms were difficult to come by in the last year. Instead, headlines were dominated by ex-politicians going to jail for big-time corruption or grama niladharis being arrested for bribes amounting to a few thousand rupees. An old war on drugs also returned to the limelight, shedding the Yukthiya skin given to it by the former administration.

As the JVP-NPP enters its second year in government, the question remains: will promised system change continue to only focus on anti-corruption, or will law reform that protects fundamental rights finally see the light of day?

System change…a mirage?

One of the most watched reforms is that of the prevention of terrorism act — a law notoriously used to oppress minorities, dissidents, critics, and journalists.

Since coming into power, the government has used the act, the PTA, to jail at least 50 suspects.

The abolition of the PTA is a much-longed for legal reform as it has wreaked havoc on countless lives for decades. The NPP manifesto promised its abolition; hence the wave of disheartenment that spread when the government sought to ‘replace’ the act instead of repealing it immediately.

Activists questioned how key government figures like Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya and house leader Bimal Rathnayake who were vocally opposed to any anti-terror law had now changed their stance.

When opposing Wickremesinghe’s draft anti-terror law in early 2024, the NPP said the draft provisions were already covered by the penal code and the criminal procedures act, negating the need for a separate anti-terror law. But today, joining their predecessors, the NPP highlights the need for such a law to tackle organised crime.

More disillusionment seeped in when activists called for at least a moratorium on the draconian law. These requests went unheeded.

In a Newsweek interview this week, Dissanayake reiterated his government’s commitment to “repealing and replacing the PTA with legislation that balances legitimate security concerns with civil liberties.”

“Bad laws rushed through will create new problems — we have experienced this in the past...We will act. And act soon,” Dissanayake had said.

The Examiner learns that the committee tasked with drafting a new anti-terror law met 33 times over the past year. Led by Rienzie Aresecularatne PC, a leading lawyer, and consisting of human rights lawyers and state officials including from the military and police, they were tasked with balancing the security of the country with the security of the individual. A new draft was handed over to the justice ministry in November. The latest official update is that the draft is being translated to Tamil and Sinhala, after which it will be presented for public comments.

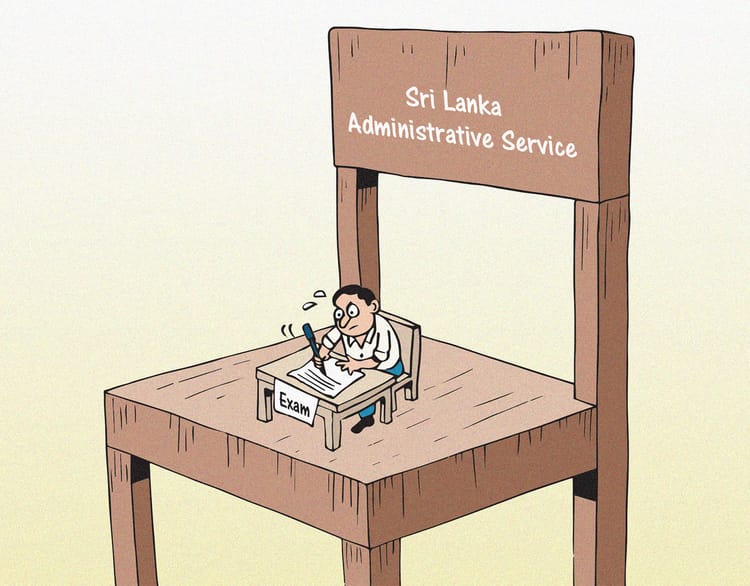

System change…for lawmaking?

The committee to draft a new anti-terror law is one of fourteen committees that the justice ministry has appointed to handle legal reforms. A few of them, like the committee to reform the muslim marriage law or MMDA, are old ones that have been reestablished under this government.

Lawmaking in the country has failed to follow a consistent pattern. With policy decisions lacking continuity between regimes, major law reforms were closely tied to the political whims of the executive.