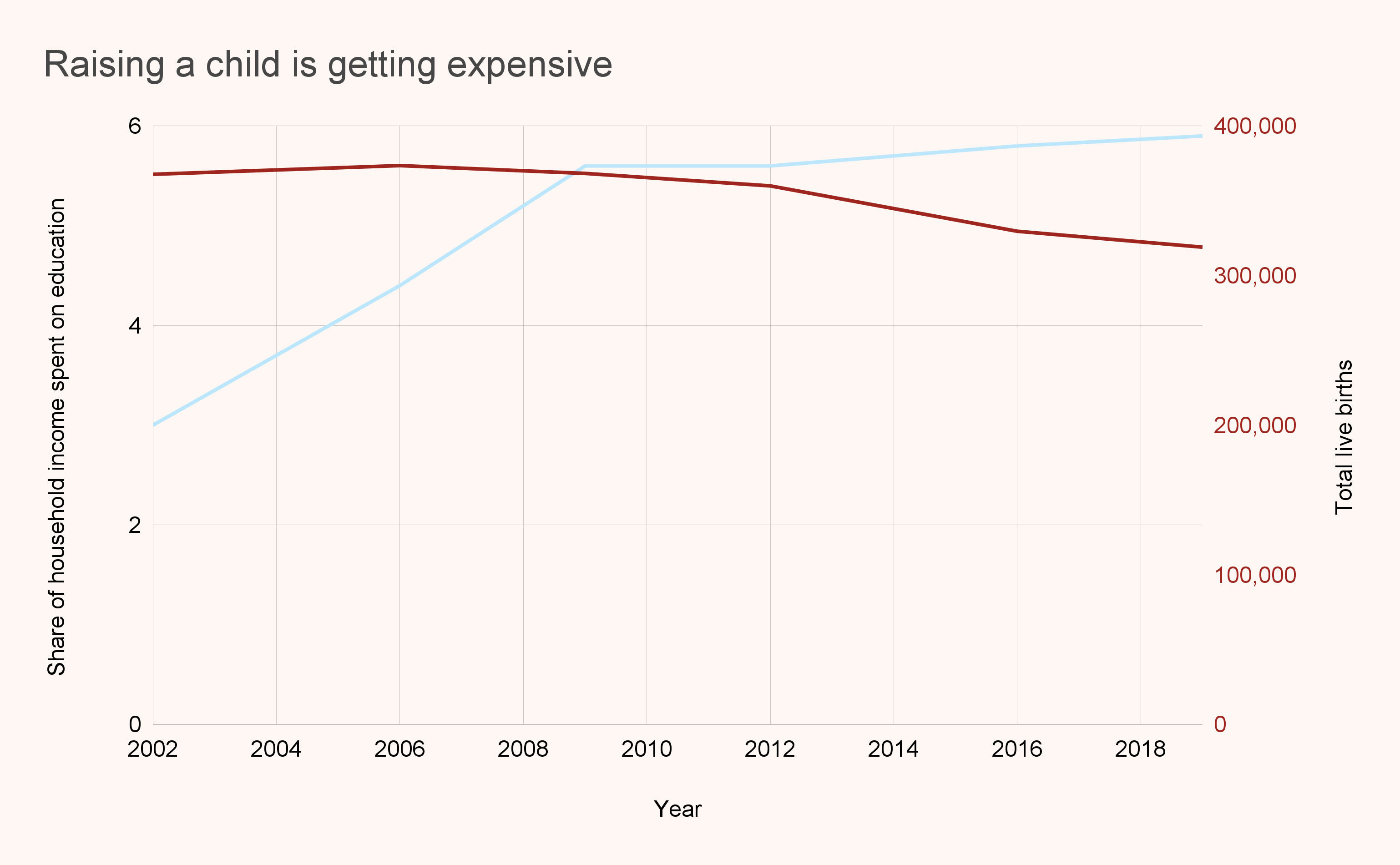

The latest census data shows that Sri Lanka’s birth rate fell by a third in the last seven years. Experts say that the numbers are concerning. A rapidly declining birth rate will fundamentally transform society and the economy.

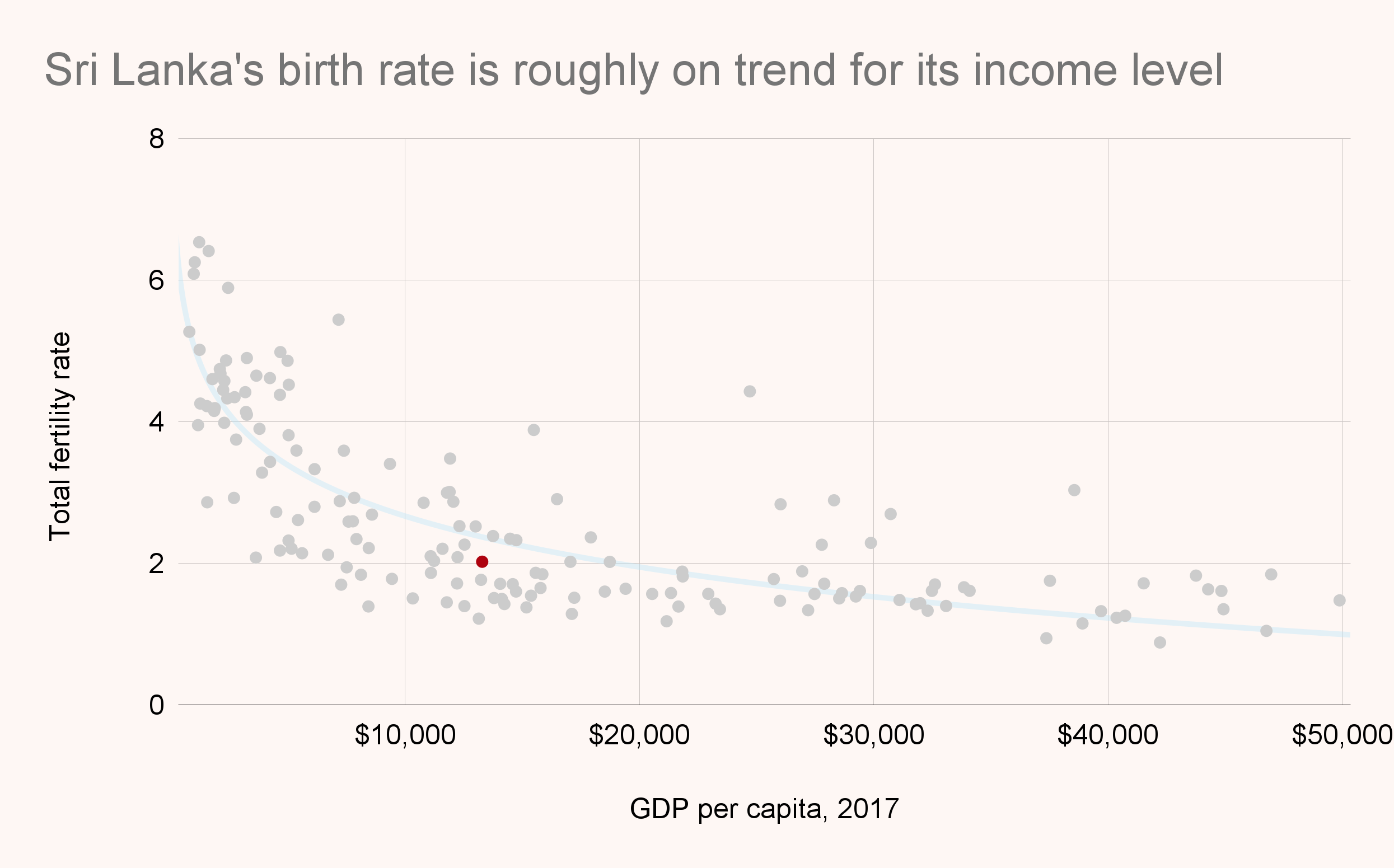

According to Indralal De Silva, emeritus professor of demography at Colombo University, the time to worry is now. Sri Lanka’s last official data on the total fertility rate — the number of children a woman gives birth to — is only from 2016: 2.2 births per woman. He thinks that fertility will continue to decline for “some time”, though he’s unable to predict until when.

De Silva isn’t the only one ringing the alarm bells: demographers and doctors The Examiner spoke to have the same view. Dr. Harendra Dassanayake, head of the perinatal society, says they’re observing reduced admissions for delivery.

When births dropped during the pandemic years, in 2020 and 2021, Lakshman Dissanayake, a demography professor, wasn’t worried. Couples typically have fewer babies during times of crisis.

But the upsurge in fertility he expected afterwards, when the country returned to “normal”, never came. “Unfortunately, we experienced a sequel to Covid-19 — the economic crisis from 2022.”

The economic collapse contributed to rising living costs, a surge in inflation, unemployment, and shortage of essential goods. These in turn affected households’ confidence in the future.

“So, many families try to delay or avoid having additional children due to economic hardships and the psychological stress that comes with them.”

With the economic crisis, also came the migration of adults of reproductive age. “A substantial minority is absent from the country. A combination of these factors contribute to lower fertility intentions,” reasons Dissanayake. Thus, the steepest drop in births occurred between 2022 and 2024.

While conditions may have improved a little, the trend to migrate has not. In 2024, over 300,000 people migrated for work, a significant increase from the pre-crisis number of just over 200,000.

Dissanayake thinks the birth rate numbers reflect a “structural fertility decline”. He believes the fertility rate would oscillate at replacement level, 2.1, in the future too — even if the economy recovers.

Replacement-level fertility is the average number of children a woman needs to have for a population to replace itself across generations, which is approximately 2.1 children per woman in developed countries.

“This isn’t temporary,” he warns.

Changing times, changing mores

However, Dr. Pavithra Jayawardena, a gender and migration expert, believes that the declining birth rates is a “wider spread phenomenon” than skilled worker migration after 2022.

With women’s role in public life increasing, Jayawardena says that “traditional thinking” about marriage is changing.

“This is a very interesting time that we are living in. The speed of change between generations is very visible at the moment. So, I think from a gender perspective, how women think about themselves, their role, their liberty, their desires, are slowly but surely changing.”

Motherhood is a more conscious decision for women now, she observes, adding that in Sri Lankan society parenthood and motherhood are taken “very seriously.”

“You compromise 100 percent of yourself to do it.”

Yet, modern women also have educational and career goals. Thus, women in South Asia are playing a “balancing act”, balancing expectations around marriage and children with accomplishing their other desires. They’re opting to have children later in life, or not at all.

Fertility clinics are among the first to notice that women are starting to explore their options. Egg freezing technology has been available for decades. Women used to freeze them entirely for medical reasons, specifically due to infertility caused by cancer treatment.