“In some ways you want a boring budget,” says Yolani Fernando, an ex-Treasury staffer who now heads Arutha, a think tank. “On the fiscal side, this budget is boring. That's a good thing. It means there is policy continuity.”

“The rest of it isn’t bold. You're staying on the track, going as fast as you were in the past. But that’s not going fast enough for seven percent growth.”

In the budget speech, Anura Kumara Dissanayake, wearing his finance minister cap, made the goal clear: “an economic growth rate of over seven percent in the medium term.”

Is the math math-ing?

Parliament’s public finance committee also worries the budget may not boost growth enough to meet the target. The committee’s budget report, published today, says the budget “stays well within the requirements” of the IMF programme.

But, one concern is “the accuracy of GDP growth forecasts.” For 2026, the government projects a 4.5 percent growth rate.

The committee suggests the government’s forecasts might be overly optimistic, citing that they’re a third higher than those of the World Bank and the IMF. That said, World Bank and IMF forecasts have been overly cautious in recent years.

The government’s ability to deliver on its seven percent growth target largely relies on spending the capital expenditure budget — the one used to build things, rather than the recurrent spending used for salaries and interest payments.

The government targets a capital spending increase from 3.2 percent of GDP this year to 4 percent for next year.

But Fitch warns that’s not enough as this year, actual capital spending was a lot less than originally planned. The rating agency says that shortfalls in implementing planned investment spending can weaken the economy’s growth potential, making longer-term fiscal consolidation more challenging.

Shiran Illanperuma, a political economist, adds that the quality of capital expenditure determines its impact on growth. He worries that some capital spending, though important for immediate human welfare, may not have a major impact on long term growth. For example, the growth impact of road construction is likely higher than renovating town halls.

He further argues that Sri Lanka needs far more investment to reach the seven percent growth target. He calls for greater investment in public housing and public transportation, especially for industrial workers, who migrate to urban areas. Unfortunately, these have not been addressed sufficiently in the budget.

“I was disappointed, I felt like I didn’t see synergy between the populist aspects of the budget like rural poverty alleviation and the growth aspect of the budget. Normally those two things are presented as an almost zero sum game, where you choose one or the other,” he said.

The government tries to do both, “but it just ends up feeling like lip service to both.”

There is greater credibility and thus confidence about revenue. Since the economic crisis, after many years of overoptimistic revenue estimates, estimates of government revenue and actuals have been much more congruent.

Analysts consider the assumptions driving estimates for next year are also broadly realistic. The budget projects excise tax earned from vehicles to reduce substantially. Anushan Kapilan at Verité Research notes that this makes sense, as “last year’s pent-up demand returns to normal levels.”

However, he also says that some revenue estimates like those for VAT threshold reduction are not available in the budget.

Realistic budgeting has earned the government some degree of market confidence. Fitch, in its budget statement, is cautiously optimistic, saying “authorities remain committed to reducing government debt/GDP over the medium term.”

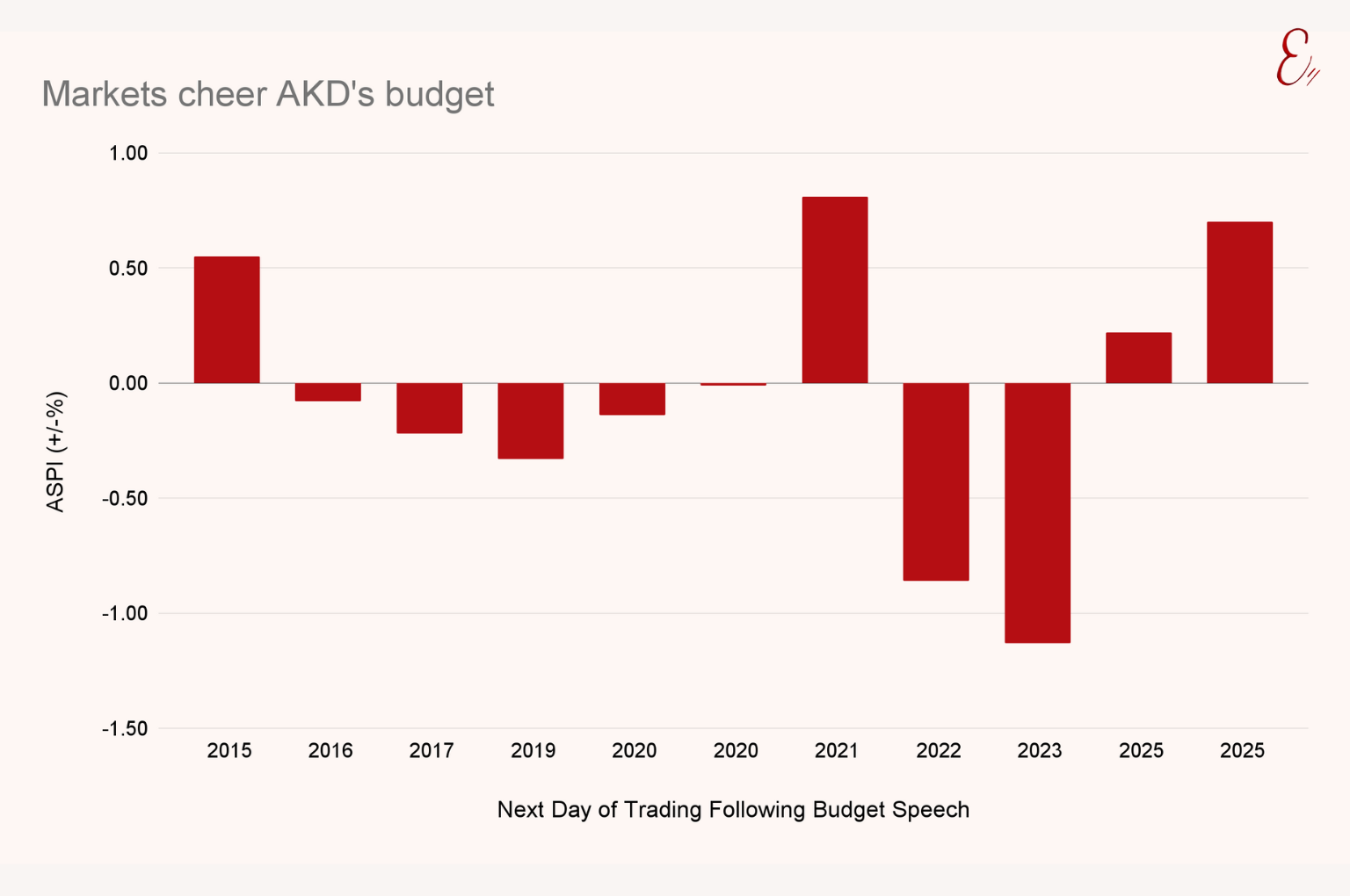

Markets cheer

Fitch’s statement is a positive signal for improving Sri Lanka’s credit rating, and thereby unlocking foreign investment. Rating upgrades can help Sri Lankan firms and financial institutions access markets, and the government to raise international financing at a cheaper rate, notes the public finance committee.

Navin Ratnayake, research head at John Keells Stock Brokers, hopes for an improved credit profile by mid-next year, which could unlock foreign investment. He says that a rating upgrade would “make a big difference in terms of unlocking funds.”