Elder care in Sri Lanka is changing. As the island’s population ages, youth migrate, and the cost of care rises, this Examination asks what elders want. And whether their wishes can keep pace with society’s rapid changes.

Before Myrna De Silva’s husband passed away, she dreamt of retiring among the misty hills in Kandy together. After he died and her only child migrated eight years ago, she made the decision to move to an elders’ home. Today, she’s paying for a room in the women’s wing of the Grace Perera Home in Dehiwala. She shares the wing with both paying and non-paying residents, as the home has a charitable arm.

At the time De Silva’s daughter was migrating, those around her balked at her choosing an elders’ home for her final years. Relatives offered her a place to stay.

“But that wouldn’t work out. It will work out for some time. But after a time, you cross paths. This is the best place. I’m independent. I’m well looked after. So that’s the best thing,” says De Silva.

Sri Lankans have always looked overseas for greener pastures, especially in times of crisis. De Silva’s daughter left eight years ago — an era of stability compared to the collapse of 2022, brought about by the economic crisis. In the first half of that year, Sri Lankans queued up for fuel and milk powder. In the second half, they lined up outside the passport office, refusing to accept a future of uncertainty on the island.

As they boarded planes to the Gulf, or more permanently to the West, they left behind their parents and other elders. Communities have changed, with both husband and wife engaging in formal work. Unpaid care work that may have traditionally come from a stay-at-home wife is no more. To add to the challenge, the cost of caregivers continues to rise — in Colombo about 70,000 rupees to 150,000 rupees per month.

As a result, interest in elders’ homes is rising. Grace Perera, where De Silva lives, receives about four calls per day. But the home is at capacity. Since 2022, the home’s telephone is ringing more often.

“These days, many children are abroad and they want to put their parents in a home. They can’t take their elderly parents there, so they find homes. We have so many elders who came in like that,” says Mala Samaranayake, the home’s secretary.

The Examiner started this story with one key question: what do elders want? Stories like De Silva’s are rare — she independently made the decision to seek elderly care, walking through the options with her daughter. Others had different stories to tell, with one common thread: money was controlled by the children and decisions were made only when push came to shove.

Chandani (name changed) doesn’t yet require a fulltime carer. At 72, she manages with a domestic worker. But she has stopped driving, a decision that hinders her mobility. She now only goes for her volunteer job twice a week.

Her husband passed away three years ago, and her two children have permanently moved overseas. Her immediate concern is loneliness. “It’s very difficult when you live alone. You can’t bear that loneliness. I was under a lot of stress and depressed due to it. I’m only now slowly getting out of it. I think nobody should go through that.”

In addition to the loss of companionship, she mourns the creeping loss of her independence.

“So far I manage by myself. But I have an insecurity where health is concerned. What do I do if I fall sick and I can’t do my own work? I don’t want to bother the children. My relatives have their own lives. So, what do I do? Do I go to the hospital? Do I go to a nursing home? If I am unconscious, how are they going to find me?”

Planning for the end-game

These circumstances have her constantly worrying about her future, which she says isn’t “100% certain” as she’s yet to prepare for her final years. With her children gone, she’s unable to turn to someone to discuss her worries with, or to start forming a plan.

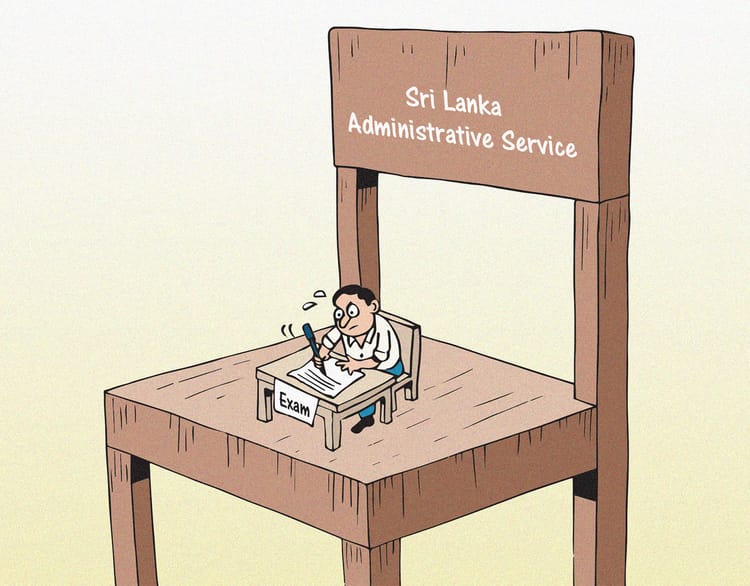

Dr. H. Yakandawala, who operates a chain of elders’ homes in Colombo, observes that in Sri Lanka, people don’t make a decision about their final years until the “very end”, when they can’t manage by themselves any longer. “[Preperation] is not in our culture.”

Often a serious fall leading to immobility forces a decision — from the children. At this point, elders don’t have much of a say. They’ve given their savings away in dowries and gifts to the next generation.

Nearly 20 percent of the country’s population is elderly, last year’s census data shows. In sixteen years, one in four Sri Lankans will be over the age of 60. The old-age dependency ratio in Sri Lanka is also rising, with 52 dependent older persons for every 100 working-age individuals.

He recommends that people start planning for their retirement years at least in their mid-40s, especially accounting for the expenses involved. “Sri Lanka should develop such a culture,” he says, adding that an individual would need about 20 to 40 million rupees for their retirement years to afford a mid-range to luxury care. Permanent residency at an elders’ home ranges from 15,000 to 750,000 rupees per month.

Dr. Yakandawala adds that lifestyles have changed in the almost two decades since he started Village 60 Plus. Elders are forgotten in the hustle and bustle of daily life: “People are busier now and no one is at home to look after their parents — or even talk to them.”

He calls old age loneliness the “biggest issue” in Sri Lanka, as it is primarily responsible for dementia: “Dementia is the killing problem now. I advise people to decide on their own before they reach this stage.”